At this point in 2007, Rudy Giuliani was the front-runner for the GOP nomination | #212 - March 26, 2023

Every primary is different from the training set

Happy Monday, everyone. This is a short dispatch from vacation.

Last week, I wrote about how opposition to Trump is a classic coordination problem. There are too many self-interested actors vying for the GOP nomination that they cannot effectively coordinate to stop their least desirable outcome from coming true: collectively losing to Donald Trump when one might beat him one-on-one (read below).

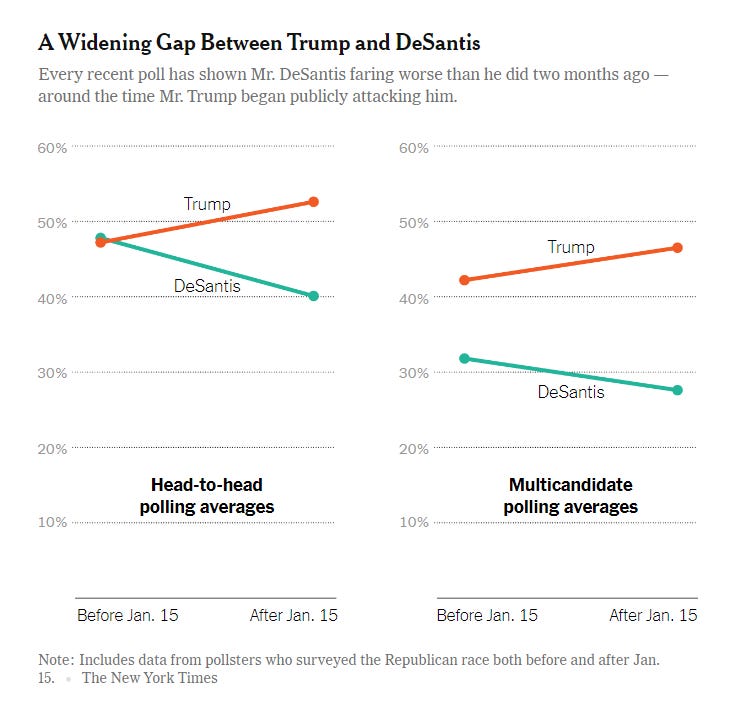

In the week since I wrote this, the prospect of a single candidate defeating Trump has declined. The average of polls, according to the Times’ chief political analyst Nate Cohn, shows Ron DeSantis, Trump’s most formidable appointment to date, slipping nearly 10 points in head-to-head polls from early January to February through March:

The precise reasons for the decline are unknown, empirically speaking. Pollsters cannot effectively resample the same people to ask why they have changed their minds — if, in fact, they have (more on that in the last bullet point below). Some reasonable hypotheses are:

Many Republican primary votes blamed Trump for the party’s worse-than-expected performance in the House and Senate midterms last November, causing them to look elsewhere for a candidate who could lead the party in a new direction.

Trump has gone on the offense — calling DeSantis a groomer and blaming him for Florida’s higher-than-average death rate from covid-19 last year — but DeSantis cannot effectively counter Trump’s attacks because he has not announced his presidential bid yet.

DeSantis has stumbled, claiming weeks ago that the Russian war in Ukraine is a “territorial dispute between Russia and Ukraine” that the US should not “[become] further entangled in”. Last week DeSantis backtracked and called Vladimir Putin a “war criminal” — but the damage may have already been done.

Maybe the polls are reacting to noise in who is responding to them, rather than who a representative set of primary voters prefer. It is reasonable, for example, to expect that Trump supporters who were upset about the midterms did not want to talk about politics in November and December. That could have artificially decreased his support in the polls — a form of polling non-response by primary vote preference.

The last point is worth considering as a serious possibility. Most polls of primary voters are national surveys that are simply subset to the Republican electorate — be that people who say they are Republicans and might vote GOP next year to registered Republicans on the voter file. These national surveys are usually weighted to benchmarks from previous polls — such as is the case with eg CNN’s polls with SSRS. Their poll is weighted to…

reflect the estimated distribution of self-identified Republicans and Republican leaners by gender, race, age, educational attainment level, region of country, population density, political ideology, Republican partisanship, voter recall, and voter registration status based on CNN’s most recent political benchmarking survey, as well as Pew Research Center's NPORS figures for religious affiliation and frequency of internet use. The CNN benchmarking survey was conducted by SSRS via web and phone from September 3-October 5, 2022, implementing a full probability design via Address-Based Sampling (ABS).

This means there are no controls for, eg, 2016 primary voter preference. There is no way to know if 2016 Trump opposers are answering at higher or lower rates over time. And maybe you don’t want to weight by that anyway (I wouldn’t) but it means that election analysts also cannot rule out that non-response is driving some of these dynamics.

The bigger picture

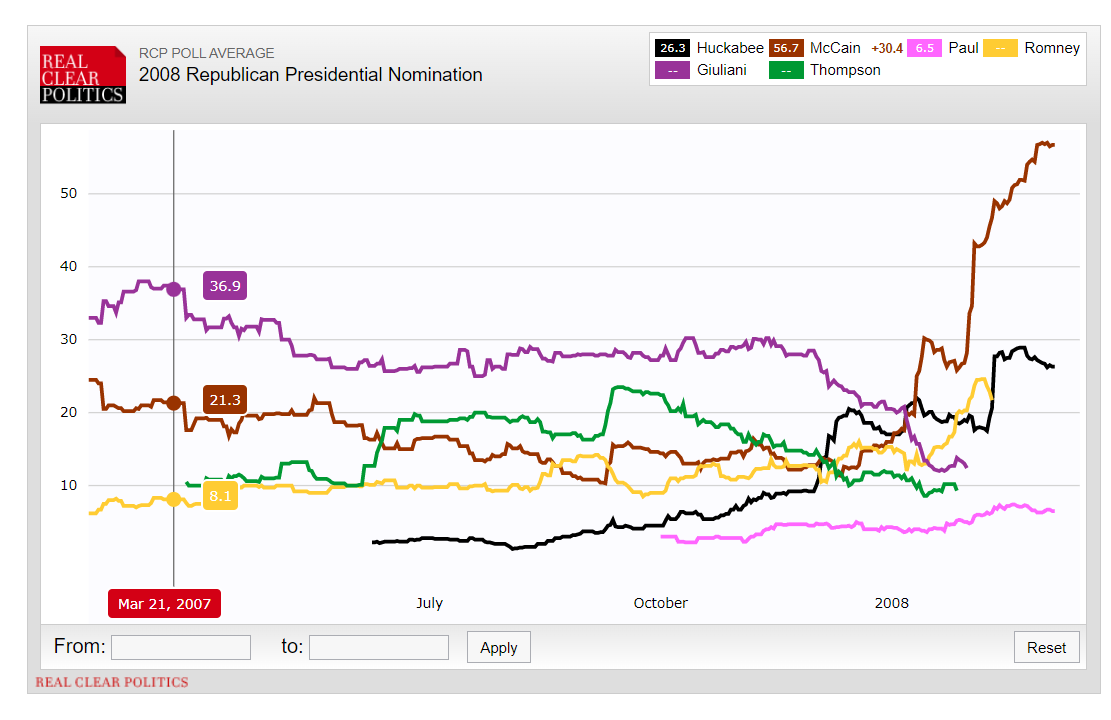

The bigger picture here is that early primary polling is only a rough guide to how the primary is going to evolve over the next year. In 2008, for example, Rudy Giuliani (yes that one) was leading the Republican field for the GOP nomination by over 15 points. But he ended up winning just 3% of the vote in the Iowa Caucuses, 0% in the Wyoming state convention, and only a single county in New Hampshire. He withdrew from the race before February.

And in April 1972, Democrat George McGovern had only 5% support in Gallup’s tracking polls. But he went on to win 25% of the popular votes for the nomination (and was crowned the winner after a raucous party convention). Ditto Jimmy Carter’s 1% in early 1975.

Of course, early polling is not useless. But it is only a rough, general guide to the contours of the primary process. Historically, the flow of the campaign has been shaped both by sharp punctuations — scandals, candidates dropping out, surprise debate performances, and other events — and slow, steady increases in support for lesser-known candidates as people get to know them.

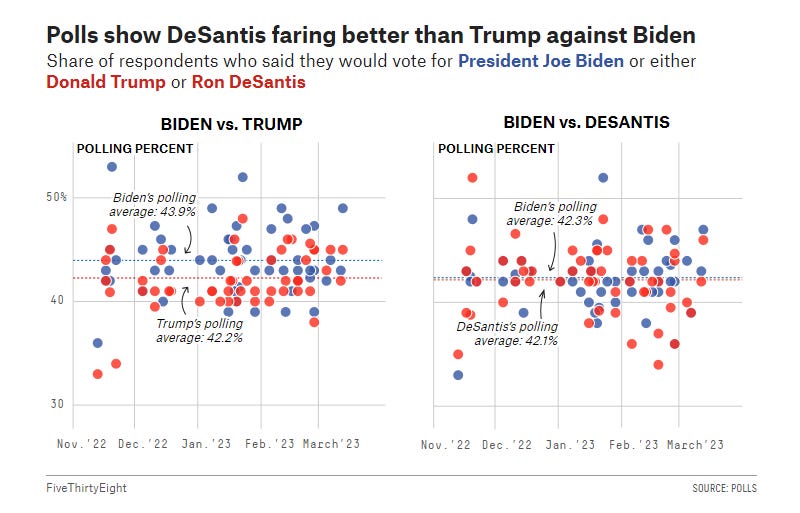

This was, of course, why I warned people against over-interpreting the polls in December of last year and January of this one. The pundits were all aboard the hype train for DeSantis (see below) when it was clear it was too early to crown him either the winner or even the presumptive winner.

Equally, it is not time not to write him off. DeSantis has the advantage of being Trump without the specific baggage the former president drags with him. That might be appealing to electability-minded Republican voters. But it does not give him a golden ticket.

One last point on this: The dismission I’ve heard of Ron DeSantis most often is that he is Scott Walker in 2016: a moderate, electable alternative to a risky nominee who does not have the personality or charisma to win. I’m not sure if this is true. Notably, DeSantis is polling better than Walker, who maxed out at around 13% in the late Spring of 2016. Yet DeSantis is at 30-35% today, depending on how you average polls together.

Either way, I am relatively sure we will get to test this theory in the coming months. A Super PAC-aligned DeSantis has recently hired an array of figures from Ted Cruz’s 2016 presidential primary campaign. (Though he did lose to Trump, he won second place — and given that Ted Cruz is who he is, that may have been quite an accomplishment by his staffers.)

This is a reminder not to get too caught up in the polls or the conventional wisdom. It is an unsatisfying answer, but sometimes, things change. A good analyst is ready to be surprised.

…

Talk to you all next week,

Elliott

Subscribe!

Were you forwarded this by a friend? You can put yourself on the list for future newsletters by entering your email below. Readers who want to support the blog or receive more frequent posts can sign up for a paid subscription here.

Subscribed

Feedback

That’s it for this week. Thanks very much for reading. If you have any feedback, you can reach me at gelliottmorris@substack.com, or just respond directly to this email if you’re reading it in your inbox.