An analysis claiming one million voters switched to the GOP last year was fatally flawed

The authors misused voter file data, conflating estimates of party ID with real changes in registration. The error was fixed by other analysts who find parity in party-switching since 2020

On Monday, the Associated Press reported that “More than 1 million voters across 43 states have switched to the Republican Party over the last year, according to voter registration data… A political shift is beginning to take hold across the U.S. as tens of thousands of suburban swing voters who helped fuel the Democratic Party’s gains in recent years are becoming Republicans.”

The bombshell story was shared far and wide by election analysts, political reporters, and even some politicians. Texas Governor Greg Abbott tweeted them matter-of-factly to his followers; Florida Senator Rick Scott said the report was “another sign of the red wave coming this November as Democrats continue to go full force on their radical agenda.”

There’s just one huge problem: the reported shift is not actually real.

To understand why, we need to explain how this “voter registration data” works. Every state maintains a list of people who are registered to vote in its elections. These lists contain records of, among other things, when real people registered, what age they are, where they live, and — in states that ask, which is not all of them — what party they want to register with. These individual state reports get compiled by national companies into one singular “voter file” that can then be bought and analyzed by candidates, party activists and, as in this case, news outlets.

The Associated Press conducted their analysis on the voter file produced by a firm called L2. The AP examined a subset of nearly 1.7 million people across 42 states who registered to vote within the last 12 months.

That is all straightforward so far, but deciding who among that set is a party switcher gets a bit dicey.

To determine whether any voter is a Republican, Democrat, or something else, L2 relies on either (i) the person’s stated party registration or (ii) in jurisdictions where no registration is listed or for people who don’t volunteer one, a predicted probability of what party they belong to. These predictions come from statistical models trained in part on other people in the voter file, in part on survey data, and in part on actual results of elections.

Now, while modeled party scores are extremely valuable to parties, candidates, and organizations, they are not directly comparable to party registration. To quote from a report released today by Catalist, a competing voter file company:

Partisan modeling .. is not as concrete as party registration, which is based on individual-level decisions on voter registration forms. Modeling, by contrast, is highly dependent on polling and analytic decisions related to demographics, geography and prior election results, along with many other factors. Therefore, it is certainly possible (and in our view, likely) that partisan modeling would suggest differences over time that are not necessarily seen in the raw registration data.

This means it’s possible that instead of the AP counting just people who have actually changed their party registration, they could also be counting:

Voters who were modeled by L2 to be Democrats or Other but registered as Republicans; and

Voter who registered as Democrat or Other but who get modeled by L2 as leaning Republican, perhaps because of either:

Polling data that indicated a shift away from Democrats among certain demographics or in particular geographies; or

Election results that showed shifts from Democrats in certain jurisdictions

To validate L2’s estimates, Catalist turned to their own records to produce tabulations of party-switchers that do not include modeled scores. Instead, since Catalist maintains historical party registration records for every registered voter they can compare apples to apples.

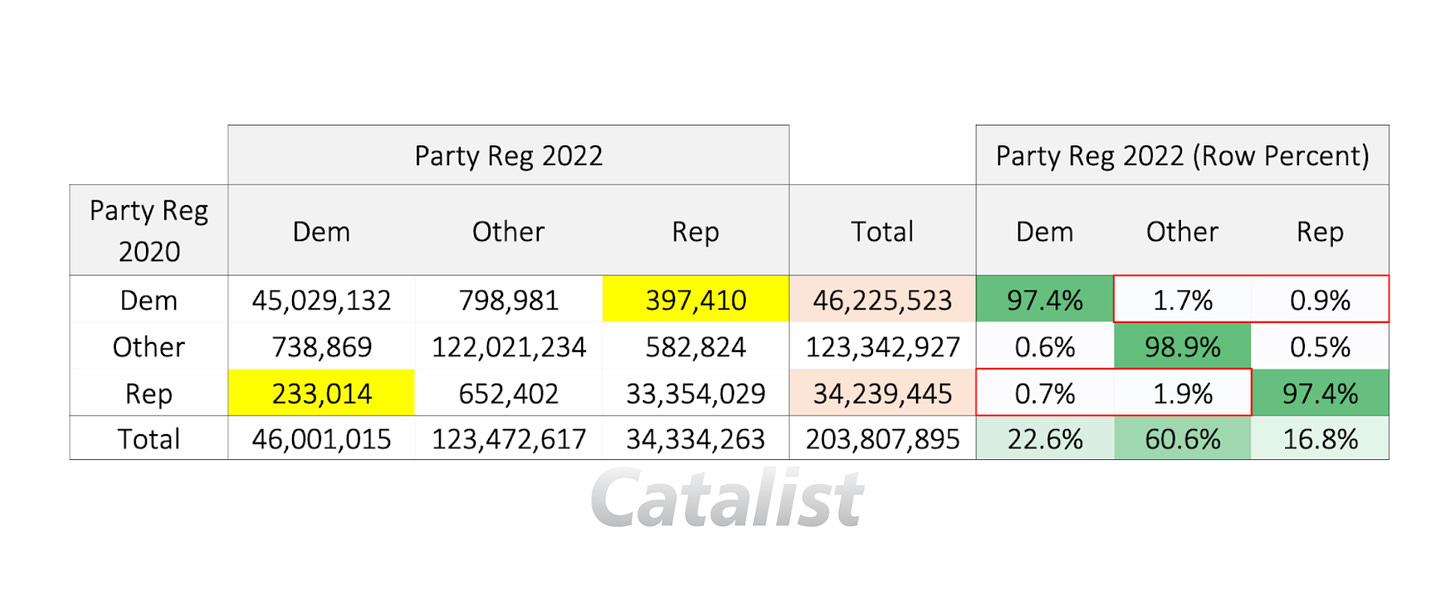

According to the Catalist voter file, since the 2020 election:

2.6% of Democratic registrants have “defected,” with 0.9% switching to a Republican registration, and 1.7% switching to Other.

The exact same percentage – 2.6% – of Republican registrants also defected, with 0.7% switching to Democratic, and 1.9% switching to Other.

These numbers are summarized in this table:

In summary, Catalist writes, “we do not find anything in this analysis that would support the conclusion that current changes in voter registrations should be a worrying sign for Democrats.”

On the on hand, we may view the AP story as yet another example of concerningly low levels of statistical literacy among political journalists. And while, yeah, to be fair, not everyone can have a PhD in political science like the authors of the report, people reporting on voter files ought to understand how they really works.

Whereas voter file firms are generally careful to note the limitations of their work, journalists are less discerning. Steve Peoples and Aaron Kessler, the AP journalists responsible for the story, wrote that the L2 showed:

nowhere is the shift more pronounced — and dangerous for Democrats — than in the suburbs, where well-educated swing voters who turned against Trump’s Republican Party in recent years appear to be swinging back.

and that

Over the last year, nearly every state — even those without high-profile Republican primaries — moved in the same direction as voters by the thousand became Republicans. Only Virginia, which held off-year elections in 2021, saw Democrats notably trending up over the last year. But even there, Democrats were wiped out in last fall’s statewide elections.

and, finally,

The AP found that the Republican advantage was larger in suburban “fringe” counties, based on classifications from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, compared to smaller towns and counties. Republicans boosted their share of party changers in 168 of 235 suburban counties AP examined — 72 percent — over the last year, compared with the last years of the Trump era.

It turns out that none of these conclusions stand up to statistical scrutiny. Instead of voters in these places changing their party registration, the Catalist data suggest that L2 is likely using current polling and recent election data to generate a change in party modeling — and the AP is misinterpreting that as the registration figure.

That is pretty concerning, as far as telling people the truth goes, since the AP is the one reporting the trends, not L2. And this dovetails with something broader about the state of statistical political analysis today: The people doing the data work seem to be to be, on average, smart straight shooters — but then you have ideologues, partisans and click-hungry reporters with their own preconceptions injecting what is otherwise pretty sound analysis with a lot of bias.

Take the final paragraphs of the AP story:

39-year-old homemaker Jessica Kroells says she can no longer vote for Democrats, despite being a reliable Democratic voter up until 2016.

There was not a single “aha moment” that convinced her to switch, but by 2020, she said the Democratic Party had “left me behind.”

“The party itself is no longer Democrat, it’s progressive socialism,” she said, specifically condemning Biden’s plan to eliminate billions of dollars in student debt.

The implication here is that a lot of voters — a whole million of them! — feel this way and are changing their party registrations to match their newfound feelings of alienation from the Democrats. And the AP uses a bad analysis of L2’s voter modeling to prove their case.

A closer look at the data reveals the pattern is more noise than signal. While voters may be more likely to vote for Republicans now compared to 2020, they are not registering as Republicans in greater numbers. They certainly haven’t surged in the millions.

As they say where I’m from, the story, in the end, is all hat and no cattle.

WTF is progressive socialism.

As opposed to... conservative socialism? Regressive socialism?