America's founders empowered citizens to pick democracy over the Constitution

The question at the center of the fight over the Supreme Court is whether we, the people, want to make that choice

All,

Enough of you have asked for more of my thoughts on political theory (and the current moment is simply so tempting to opine on our institutions that I couldn’t say no) that I have decided to write another issue on the growing power imbalances of our institutions. The bad news is that our democracy is in a bad way right now. The good news, for what it’s worth (and that may not be much), is that we have the right to change them.

Editor’s Note: This is a post for paid subscribers. I don’t mind if you forward it to your friends and family, but I would appreciate if you urged them to sign up for posts by clicking the button below if you do so:

Since Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s passing, I have been struggling to figure out an intelligent way to contribute to the discussion over the Supreme Court. It seems like the new vacancy has left most of the people I pay attention to entrenched in their same old worldviews. On one extreme are people who think we should pack the Court in order to pass ambitious lefty policies; on the other are our neighbors who think that Trump should fill RBG’s seat with a conservative justice as soon as possible. (Needless to say, there are some people in the middle, too.)

But my thinking on the subject has evolved in a different path over the past couple of weeks. The combination of an election year with as high stakes as this one, the minoritarian control of the Electoral College and Senate (due mainly to recent levels of white geographic political polarization) and the ability for a governing minority to control two and a half branches of government (the Senate, White House and Supreme Cout) has repeatedly had me coming back to an important question: has our desire for mass democracy pushed the Constitution past its expiration date?

…

To start, let me assert that it is not up for debate whether the US Senate represents a majority of Americans. The data have clearly fallen toward the negative. Consider three empirical points:

Democratic senators represent about 13 million (5%) more Americans than Republican senators do, yet have 6 fewer seats in the Senate.

To win a majority of seats in the Senate, Democrats would need to win the equivalent of the national popular vote for senators by at least 7 percentage points. In other words, the median seat is 7 points more Republican than the country as a whole.

To win a supermajority (67%) of seats in the chamber, Republicans would need to win a hypothetical senate popular vote by just a 2 point margin — the equivalent number to get Democrats to 67 seats is 19 points.

Further, neither is it up for debate whether the magnitude of the Senate’s bias toward rural (and, currently, Republican) voters is something the founders envisioned. For one, the population disparity between the smallest and largest states has grown from nine-times in 1790 (Virginia v Deleware) to nearly forty-times today (Wyoming v California).

A complicating factor in the original design of the Senate is that, while the founders (or the bare majority that supported it) wanted an institution that gave small states a political check on the large states, they did not intend for the chamber to enshrine power in a significant, partisan minority of voters. The consequences of over-representation of rural voters are made more severe when the group of voters who are given extra power in our government all vote for the same party versus when the two parties are reasonably competitive with both the advantaged and disadvantaged groups.

Briefly: This bias evidently spills over to the Electoral College, too. Recall that it has elected the minority vote-winner in two of the last five elections — both times giving the Republicans power over the presidency when the majority of voters wanted a different outcome.

…

At this point in my rant about our government and electoral institutions, someone usually stops me to remark that the founders didn’t intend for the government to be democratic. After all, that’s the reason they established the Senate in the first place. the Electoral College exists as a check on the “democratic whims” of the people or some other such theory.

But these people are missing the point. The important question to ask is not about what the founders would have wanted, but about how we, the people—today—want to pursue self-governance. Do we really want a government that allows 46% of people to constantly oppress the other 54%? Do we really believe that the political opinions of a Wyomingite is worth 40 times as much as a Californian (and what would we think if the bias was reversed)?

Now, with a Supreme Court vacancy, this question has ascended to its highest import yet. The simple fact of our government today is that it allows one political party, representing a minority of voters, to easily wrestle control over two chambers (the presidency + Senate) out of four (add the House and Supreme Court) of our government. And they are threatening to control three out of the four. In the modern, majoritarian context of self-determination in America, that is unfair.

…

Geographic political polarization has evidently falsified the founders’ assumptions that so-called “co-equal” branches of government could hold each other accountable. The ability for a minority of voters in our country to control the White House, the Senate and Supreme Court is evidence not only that our institutions are prone to egregious violations of the principle of one person, one vote, but also that the Constitution is not doing what the framers intended it to do: slow the ability for one group of people to steamroll over another

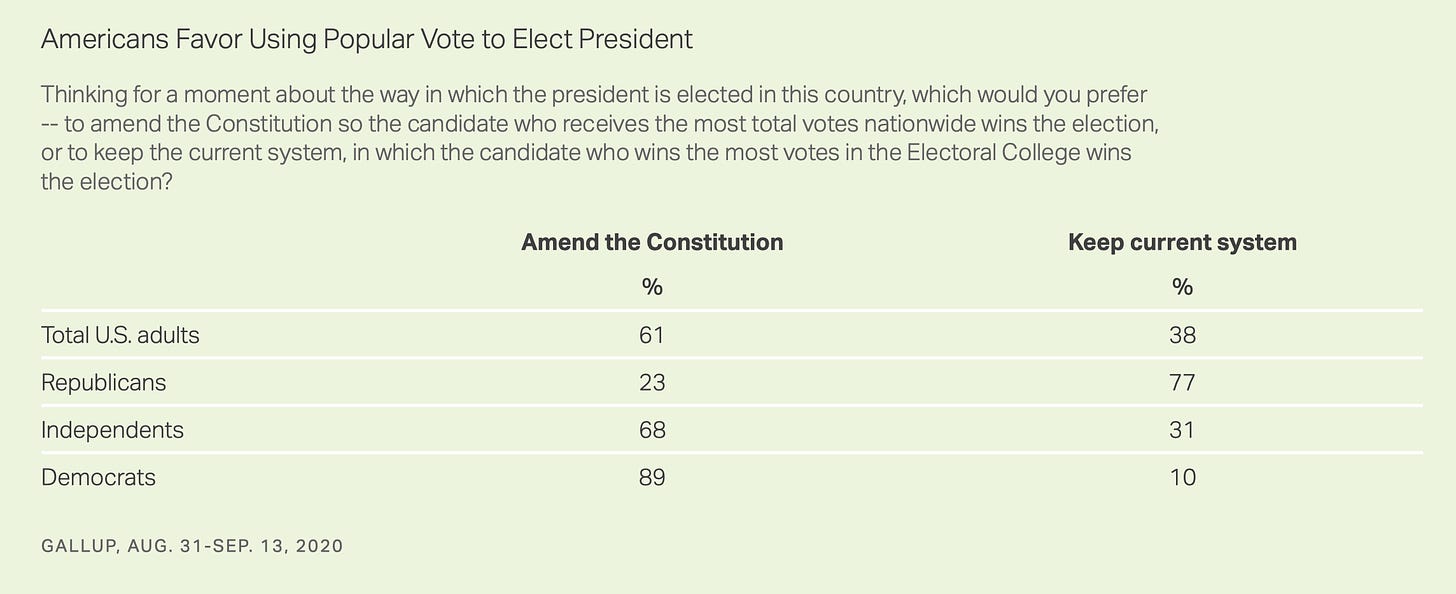

Most Americans agree that the country’s current structure of government is unfair and want it to change. A new Gallup poll finds that 61% of Americans support abolishing the Electoral College and electing the president via popular vote, versus 38% who want the system to stay as-is:

And although I could not find any polling about support for abolishing the Senate, it is worth noting that faith in our government has routinely hit historical lows over the last decade.

…

It has become increasingly clear that America’s founders failed in producing a system of government that could withstand the vicious consequences of parties, geographic polarization, authoritarianism and minoritarian power-grabbing.

Lucky for Americans, we are not totally powerless in righting the ship of state — so long as enough of us decide to do so. Some intermediate steps to remedying the crisis of confidence in our government are:

Increase the size of the House of Representatives. Until 1930, the chamber gained seats in order to represent the people more proportionally (the original intent of the House I might add). Adding more seats today would decrease the chance for a minority of voters to control its majority of seats (like they did between 2012 and 2014).

Pass a federal law to mandate that US House and Senate elections are conducted with ranked-choice voting to ensure that the people we elect to office represent a majority of voters (the machine could easily be approval voting or single-transferable vote — I don’t care, so long as it’s majoritarian). (While they’re at it, Congress should also pass a federal holiday for voting and expand the budget and regulatory power of the Election Assistance Commission.)

Admit Puerto Rico, Guam, American Samoa and the Northern Mariana Islands. as states. Besides the fact that it would decrease the over-representation of rural, white voters in the Senate, it’s also the right thing to do on principle. If they’re allowed to vote in presidential primaries, they should be allowed to vote in the general election too.

Expand the size of the Supreme Court to 15 (or, hell, why not more? judges and set their term limits to 18 years. That way, each president has the ability to appoint three judges (one-fifth) of the Court on average for each term they’re in office.

These are just intermediate steps. It’s clear that geographic-based systems of representation will never work fairly again in America; the population is just too disproportionately located in a few states and geographic partisan polarization is too extreme to ensure that the outcomes of our government math, on average, the will of the people (by which I mean the majority of voters). The only real solution is to get rid of those systems and move toward a system of multi-party, proportional representation. Everything until then is but a stepping stone on the path to a just and fair government.

Are we ready to take the next step on that path?

It is depressing that Constitutional amendments aren't really feasible. There has been only 27 amendments in our 244 year history, when will we have another one?

Bravo! Really well stated.