American democracy is screwed

Our best hope is a (very unlikely) mass mobilization of voters that favor multiparty democracy

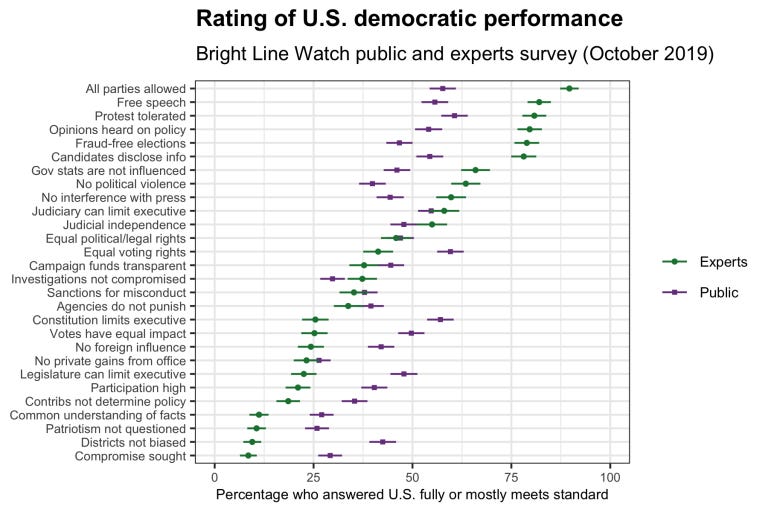

American democracy is on thin ice. A survey of experts in October of 2019 found that they rated American democracy at about a 70 out of 100, showing broad discomfort with a number of factors they define as essential to modern democracy. Only 41% of them believed that all adult citizens have equal opportunity to vote, for example, and only 26% thought that the government today was effectively limiting the president’s power to its proper Constitutional bounds.

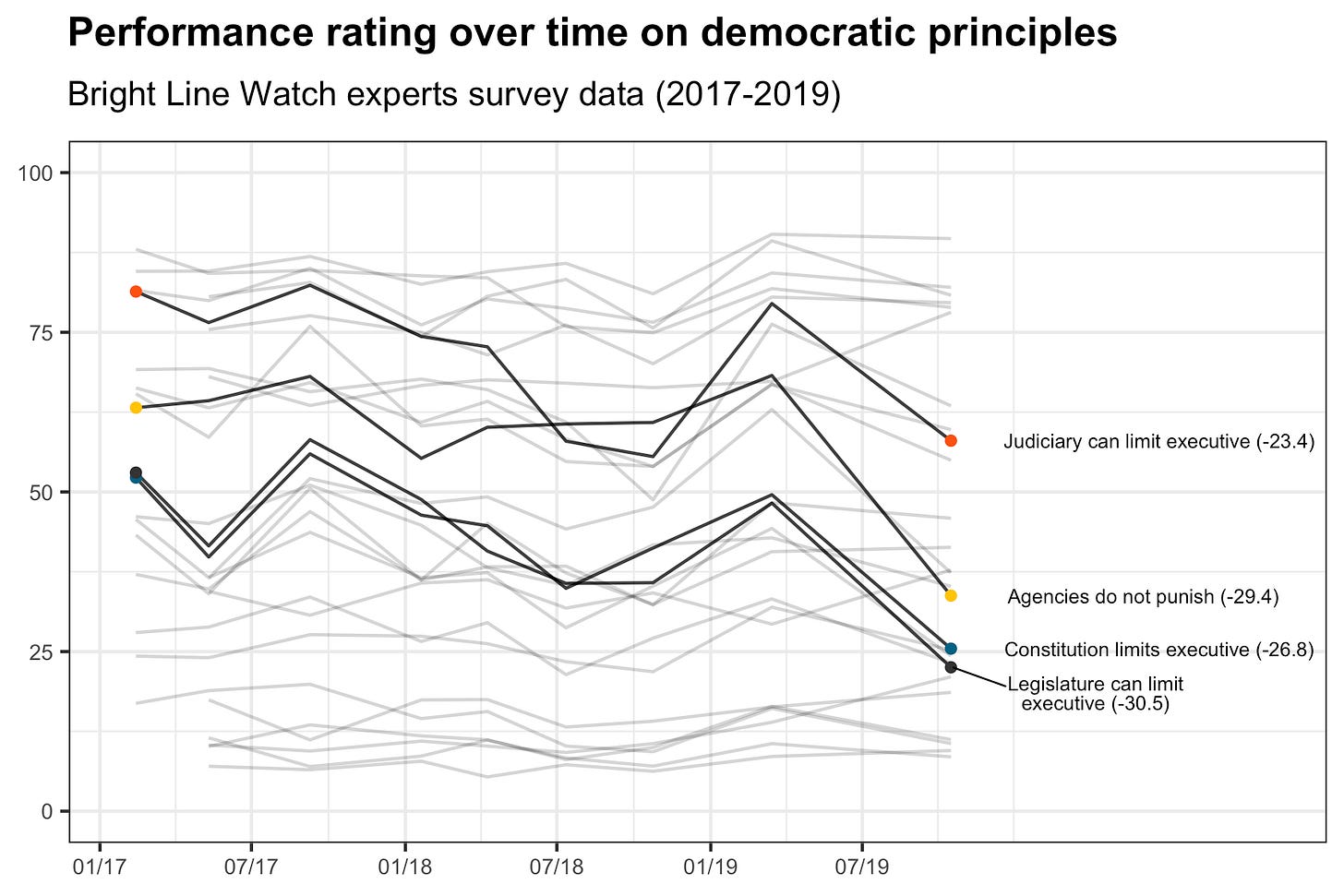

While ratings for US democracy were largely stable in aggregate, there has been some significant erosion along some measurements over the past year:

These problems can be generalized as the type that political scientists typically believe are onset by the exploitation of government rules, norms or institutions by certain bad actors. It comes as no surprise that many of these experts blame party leaders such as Donald Trump and Mitch McConnell for the instability in our politics today.

But, perhaps more pessimistically, there are also political scientists and experts who argue that these issues are inherent to our politics because they they are natural products of our political institutions, both as they were set up in 1787 and have evolved over time. And they make a compelling case that the consequences of our systems for politics, both as the practice of governing and our socio-political relationships to one another, are dire.

The study above details some of the symptoms ailing our democracy today. But what are the causes?

Such is the subject of two recently-released books on American politics. Lee Drutman’s Breaking the Two-Party Doom Loop and Ezra Klein’s Why We’re Polarized are well worth reading. They simultaneously paint a stark picture of the present of, and hopeful picture of the future for, US democracy, the dangers and instability of which worth taking seriously.

This post details my conclusions after reading the two texts. I am not hopeful. American democracy looks screwed, I attest, for several reasons:

Our electoral system incentivizes two-party politics, and maybe even its increasing toxicity.

Two-party, winner-takes-all politics have fueled hostile in-vs-out-group psychology and created two separate, irreconcilable political realities in America.

Reformers will be unlikely to succeed in establishing a multiparty democracy, the best way out of the current mess.

The anti-majoritarian nature of the US Senate will continue to be a stain on American democracy that prevents responsive government regardless of the electoral system.

Subscribe for more!

I enjoyed writing this essay for you all, despite the pessimistic tone. If you liked it, be sure to tap the ❤️ below the title and subscribe to my newsletter for more. I send out free weekly emails—similar to this one, but usually shorter and with more data—and more frequent content for paying subscribers. Just press the button below.

—Elliott

The Constitution is the biggest source of our problems

America’s current political woes can be traced back to one simple fact: The Founders built an electoral system that was inherently susceptible to two-party politics, even though they feared and hated parties. Such is the product of both features and bugs in US elections.

The Founders worried about the destabilizing role of political parties from the very beginnings of the country, Drutman tells us. He pulls some great quotes from them, such as Washington’s warning of “the alternate domination of one faction over another, sharpened by the spirit of revenge, natural to party dissension, which in different ages and countries has perpetrated the most horrid enormities” and John Adam’s much-clearer “a division of the republic into two great parties is to be dreaded as the great political evil.”

Yet they formed parties! The recent fame of Alexander Hamilton has made the early divisions between the founders a familiar story to most people familiar with American politics. He and his allies wanted a strong central government. Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, opposed, didn’t.

Such a descent into the fictionalization of political competition is evident of the pressures that America’s electoral systems exert on our elected leaders. At the Congressional level, the founders should have seen that the process of electing legislators via plurality vote would obviously lead to factions. Two-party politics are the natural result of elections that disincentivize voting for uncompetitive third-party options.

Though Drutman doesn’t get into it, it’s worth noting that while the Founders were committing the original sin of American democracy—enacting plurality elections for the US House—they also created the its other biggest problems the US Senate and the electoral college. The US Senate is an exorbitantly anti-democratic institution, not only because it magnifies the votes of smaller states (a violation of one-person one-vote) but also because it gives an outsized say to the faction that represents those smaller states. The electoral college is also inherently anti-majoritarian by design. Both issues have gotten worse over time—with the direct election of senators and binding of electoral votes to the state’s popular vote—in ways that make them worse violations today than in 1787. We’ll revisit this part later.

The two-party system that the parties created has ebbed and flowed throughout history. There is no doubt that is has recently reached one of its worse points. Americans today are less satisfied with their government, and angrier at each other, than they have ever been before (save the years before the Civil War, perhaps). It’s worth reviewing how we got here.

We’re polarized. Why?

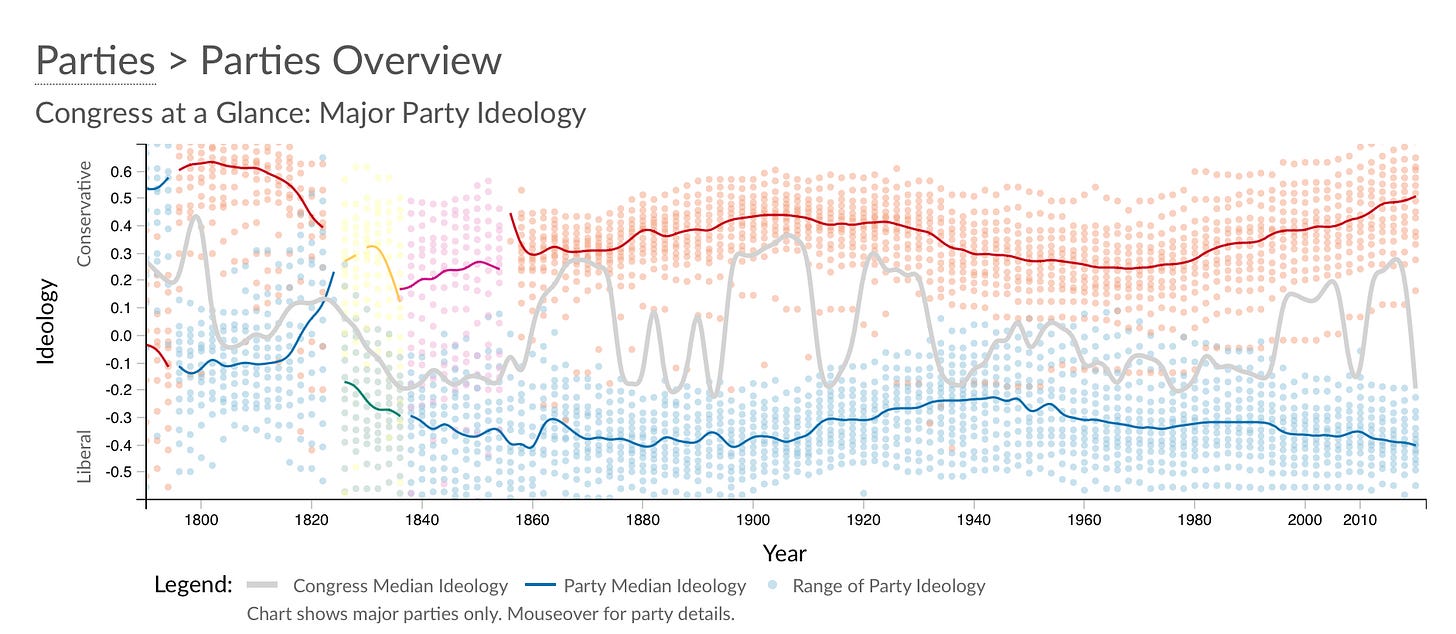

America’s political parties weren’t always so polarized. In fact, you only have to go back to the mid-20th century to reach a period of some of the highest cross-party cooperation, and mildest ideology polarization, in American history. This chart shows the average ideology of each political party since the founding:

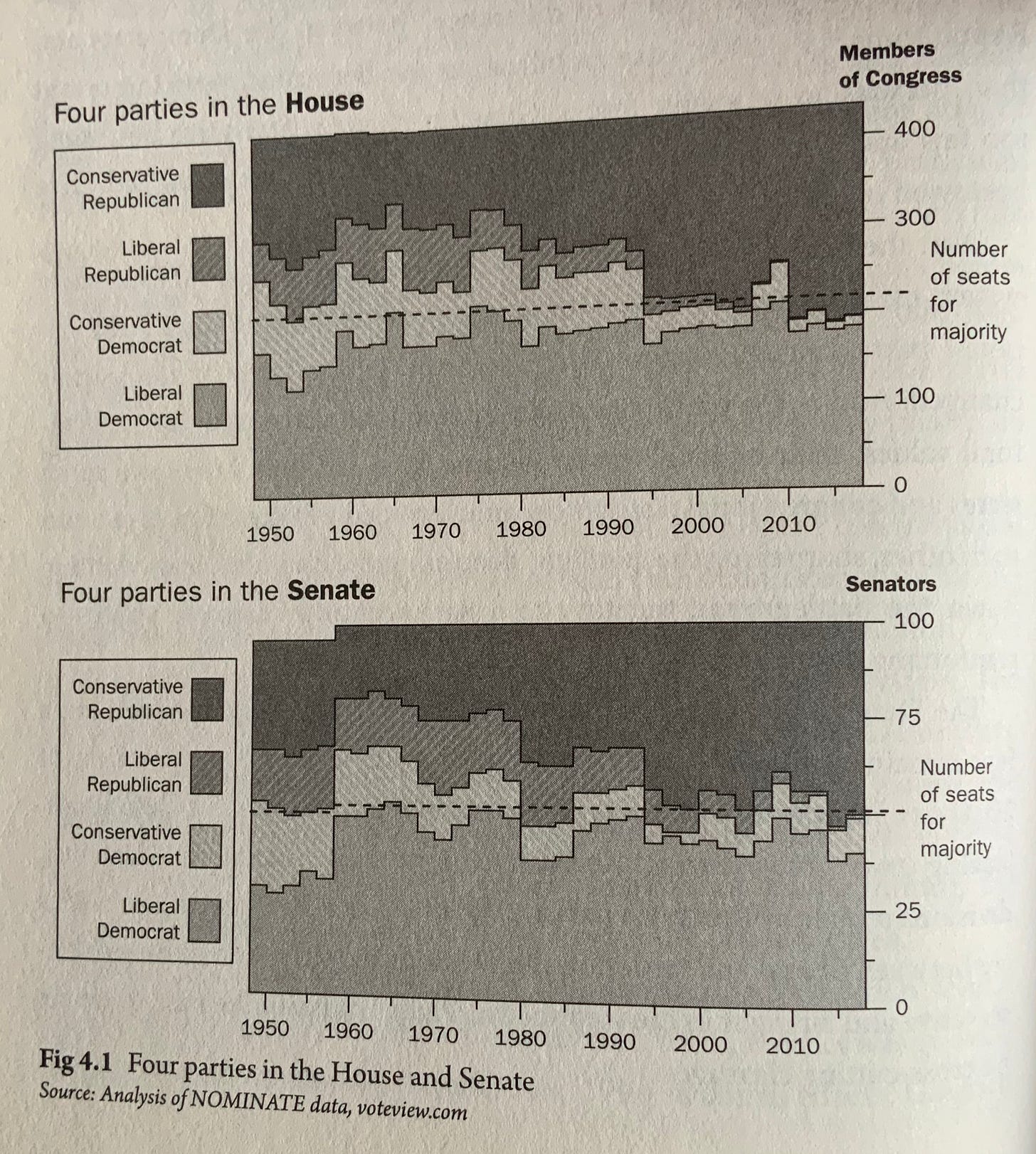

Then, the two parties were different beings entirely. In the 1960s, they both contained a mixture of ideological liberals/conservatives and racially liberal/conservative, anti/pro-segregationists. And as the party system reoriented itself around the politics of race and discrimination—with southern Dixiecrats becoming Republicans and racial liberals become Democrats—there was a brief period of cooperation in Congress.

This gets to the heart of what Klein means when he talks about polarization. He offers a simple definition by way of example:

Imagine that everyone who wants to legalize cannabis moves into the Democratic Party; everyone who wants to outlaw it joins the Republican Party, and the undecided voters are split evenly between the two parties. Now the parties are perfectly sorted…

Polarization, to Klein, is what political scientists call “partisan sorting.” It’s about parties becoming associated with a certain set of political issues, ideological labels and racial associations.

Sorting is clear empirically. From the mid- to late-1900s, the parties adopted clear ideological labels and became more polarized—or sorted—in their preferences. Drutman produces this graph of the decline of what he calls the “four parties within the two parties” over time:

But sorting isn’t just about issues preferences; it’s also about identity and association. Partisanship today has clear associations between racial groups and and openness to others. These correlations map onto things like population density and educational attainment.

And here Klein seems to set into his groove in asserting that polarization, more than anything, is about in- and out-group psychology. We think of ourselves as opposed to others in terms of demographics and class and religion and support for abortion and belief in climate change and—the list goes on and on.

Klein recounts a conclusion from political scientists Patrick R. Miller and Pamela Johnston Conover, who wrote in 2015 that “The Behavior of partisans resembles that of sports team members acting to preserve the status of their teams rather than the thoughtful citizens participating in the political process for the broader good.” Politics is zero-sum, winner-takes-all.

And here’s where Klein and Drutman’s books come together; because not all politics is zero-sum, but two-party politics definitely is. Multiparty politics, as we’ll see, can be a thing of beauty.

The two authors both trace the roots of modern political polarization—especially regarding identity-based ideology and party membership—to Civil Rights and the inflaming of our factional passions. Klein also asserts that the media and the Internet have polarized us—Fox News in particular. Partisan news channels get shares—and revenue—when people tune in to hear the nightly rant against x or share their online articles about y. And you don’t get dotted, angry news consumers by cutting down the middle; you get them by catering unabashedly and unashamedly to one side of the political aisle.

But all this news consumption has led to misperceptions about the other side. Klein recalls a study from Douglas Adler and Gaurav Sood in 2008 that found that Democrats and Republicans hold severe misperceptions about the other side. Importantly, they found that the more cable news you watched, the more severe your misperceptions were. Partisan news both targets and reaffirms our identities—this is why Klein calls it identitarian news. Social media, too, plays a role in affirming our identities. A study of 1,200 Twitter users in 2017 found that partisans exposed to news and opinions from the other side do not soften their allegiances but harden them.

Drutman’s thesis is worth reconsidering again here. He says that all this polarization—in policy preferences, in our identities in the news media and in social media—is a result of our electoral system. The parties have sorted along all these different dimensions, with the Republican Party perhaps leading the way, to maximize their the number of times they win elections. In other words: we’re stuck with a “doom loop” of toxic polarization until we fix the way we elect our representatives.

What’s the solution?

Drutman advocates for reforming America’s party system in accordance with the theory of “responsible partisans”— political scientists who attest that parties are good because they adopt a (sometimes) coherent set of differing stances, crystallizing voters’ choices and providing them with clear partners for bargaining in government.

Drutman’s embrace of parties does not blind him to their critics. Indeed, he describes the paradox of partisanship as thus:

We need some division for parties to provide meaningful alternatives and to give voters power to send strong signals. But too much division and the stakes start to feel too high. Politics becomes toxic. Partisan conflict overwhelms every issue, spreading even beyond politics, and democracy deteriorates.

I want to emphasize the last bit. Too much division and partisan conflict spreads even beyond politics and democracy deteriorates. We see this today, most notably, in that the parties have even begun to polarize around the issue of democracy reform. I think this is one of the most concerning forms of polarization, and devote some time to it below, but keep it in the back of your head for now.

So how can we decrease polarization and the stakes of partisan conflict while retaining strong parties? In short, how do we fix democracy?

This is where Drutman makes his chief prescription for fixing what ails American politics today: multiparty democracy. If the US had multiple smaller parties that were all competitive nationally, then voters would have their pick of parties that both are (a) positioned throughought the ideological space and (b) better equipped to bargain for the interests of their constituents. Multiparty democracies consistently produce more moderation and compromise in governments, happier citizens, and better representation for ethnic minorities (who have particularly suffered from America’s two-party system).

How do we save democracy?

Drutman’s solution is to institute a new a method for electing our officials called ranked-choice voting (RCV). It works like this: instead of casting your vote for House representative for just one person, you rank all the candidates you’re considering from most desired to least. When the counting starts, everyone’s votes for their first-choice candidates are tallied up. If one candidate has a support of the majority of voters, they instantly win. If not, the candidate in last place is eliminated and their voters get reassigned to their second-choice candidate. The process repeats until someone has a majority of the vote. (Here’s an old video describing ranked-choice voting, which some people call “the alternative vote” or “instant-runoff voting”.)

Drutman claims that because RCV eliminates wasted votes—the disincentive in plurality-elections whereby voting for an unviable third-party option is a waste—it allows multiple parties to flourish. This would decrease the polarization in US politics by incentivizing candidates to target their messages to a broader base of voters.

RCV would be easy to implement in America. States are allowed to change the rules by which they elect their representatives, so legislation at the state-level is all we’d need. Maine already uses RCV for federal offices and so do many of America’s cities.

Some of Drutman’s other solutions would be harder to implement. One proposal is to use RCV in multi-member congressional districts, which imposes some proportionality on the House. Another is to recreate Germany’s legislature in the House by dividing it in half, one portion for a national RCV for proportional representation and another for your single congressperson. These reforms would be more radical than implementing RCV for the current number of House districts and probably invite too much backlash, even if they would produce the more desired outcome.

How do we get there?

Multiparty democracy will be hard to achieve. According to Drutman, there are four conditions for successful electoral reform:

Reform can happen when (1) the problem is clear, (2) the solution is clear, (3) the public demands reform, and (4) a majority of elected officials believe they’ll survive or even thrive under a changed system.

Anybody who reads Drutman’s book—or, hopefully, this article—will be convinced of the problems of America’s two-party system and the clarity of the solution presented in multiparty democracy via ranked-choice voting. But that’s where the conditions for reform hit a brick wall.

I could not find any polls on ranked-choice voting nationally, but the actual results for Maine’s citizen initiative for reforming their electoral laws may be instructive here. In 2016, Maine voters passed RCV, but only by a slim majority of 52% to 48%. I don’t think a 4-point margin meets Drutman’s third condition of the public “demanding” reform. Consider that Maine is also a more liberal state, and with support for electoral reform being polarized along partisan lines, we should expect that the many of the other small and the Republican-leaning states to be against RCV.

Still, over 60% of Americans want to see a third-party, according to Drutman. So maybe there’s hope after all?

Can we get there?

I am pessimistic. I do not believe reform will be accomplished soon.

Primarily, There is currently no significant movement for RCV nationwide, or at the state-level in most large states. Politicians won’t act, according to Drutman, unless people tell them to do so—and right now, the people aren’t speaking up nationally.

I suppose RCV optimists would argue against this idea. In Maine, after all, a mass mobilization of voters overcame several challenges to RCV from Republicans after its original passage in 2016.

But nationally, the picture is not the same. Let’s sprinkle in some more wisdom from Mr Klein, particularly focusing on our psycho-social attachments to the status quo.

We—voters as well as politicians—are entrenched in our two party system today. Things like budgetary debates in Congress are almost uniformly factional. We could do away with them, as Klein suggests, but that’s yet another hurdle to stack on the list of things to accomplish before pursuing RCV.

It’s true that voters want third-parties, sure, but they don’t want to see their primary one give up any power. We have become partisans first, and probably reformers second.

What if we try something else?

Klein says we could get rid of the electoral college or circumvent it with a state-by-state compact to assign votes to the nationwide popular vote winner. Yet such measures look impossible to pass, as many independent actors in Republican-dominated state legislatures would have to vote against their interests to do so. Similar proposals such as adding 100, 200 or even doubling the number of seats in the US House, are likely to fail. Movements to admit Puerto Rico and Washington, DC as states are also likely to fail—again because they would disadvantage Republicans, who control the Senate and (for now) the White House. Which brings me to my last point.

The Senate is too anti-democratic to ignore

Even if we pass RCV for House districts and the Senate—via state-level or federal legislation—the latter will still have an extreme bias toward the Republican Party. This bias persists regardless of the voting method. The root of the issue with the US Senate is not polarization, you see, but malapportionment. Wyoming and California send the same number of legislators to the chambers, despite the latter having 70 times as many residents as the former. Because rural voters are more likely to be Republicans, this creates a severe and enduring bias toward the GOP (so long as they are the party of rural voters).

That bias is bad on its own, preventing legislation from passing Congress that a majority of people support, or helping Republicans keep their president that a majority of the people want removed from office.

But the bias would also no doubt get in the way of federal electoral reform. Recent years have shown that most of the support for measures like RCV or the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact (NPVIC) come from liberals who see the system as biased against them. Indeed, the Democrats have won the popular vote for president in four of the past five election, but only won twice—in other words, only in 60% of elections in the 21st century did the people actually elect the president. The rest of the time, the pro-rural biases of the electoral college (which is smaller than, but is sourced from, the Senate’s) skewed the election. Republicans benefit from the system today. Why would they want to fix it?

And this brings us full circle—back to zero-sum politics, partisan sorting and both issue- and identity-based ideological polarization. The very factors that ail our system today are likely to defeat mass efforts to effectively reform it.

Allow me to also make a brief segue to talk about “mass mobilization” and effectual political reform. In his new book Politics is for Power, Eitan Hersh makes the case that most of what people call “engaging in politics” today is actually “political hobbyism”, which he defines as:

a catchall phrase for consuming and participating in politics by obsessive news-following and online “slacktivisim,” by feeling the need to offer a hot take for each daily political flare-up, by emoting and arguing and debating, almost all of this from behind screens or with earphones on.

You might be thinking “but my participation is different”. Maybe you have an online following of journalist and active politicos. And maybe you do attend local PTO meetings or hold the yearly fundraiser for a local candidate for the state legislature or US House. Maybe sometimes you’re engaging in politics. But the vast majority of the time, Hersh says, you’re engaging in political hobbyism.

He’s got the receipts to prove it. Only 6% of Americans that he surveyed admitted to regularly engaging in real political activity, such as volunteering for a candidate’s campaign or a cause you believe in. Odds are, you’re more of the slacktivist than the activist.

Though Hersh presents a strategy for shifting your efforts to actually affect change, I doubt they’re all that effective. People listen to their podcasts and chat about politics because they’re interested in the horse-race and the sex-appeals of political intrigue, scandals and—yes—institutional disintegration.

The point being: even the people who support reform aren’t likely to be making their voices heard in the right ways.

We’re screwed

So, then, we’re screwed right? At least in the near-term, I don’t see any hope for fixing American democracy.

First, polarization of electoral reform has already killed bipartisan support for it—at exactly the moment when we desperately need it.

Second, the Senate and electoral college will continue to be stains on American democracy regardless of the mode of election.

And third, the political hobbyists who have jumped on the RCV train aren’t likely engaged in the activities that would actually bring about reforms.

Yet there’s that age-old adage we haven’t considered. “It’s tough to make predictions, especially about the future.” I’m pessimistic about reform—but maybe, just maybe, there are people out there who can prove me wrong.

Want to read more?

If you learned anything from this, you’ll probably also enjoy the other writing I send out via this newsletter. Press the button below to sign up!

Because reform is so unlikely I will just dig in and hope my side gains all the power.

Also do you have evidence for " Multiparty democracies consistently produce more moderation and compromise in governments..."?