Actually, data show fairly worrying trends about the US coronavirus response 📊 March 22, 2020

The virus will continue to spread without serious control measures

Welcome! I’m G. Elliott Morris, a data journalist at The Economist and blogger of polls, elections, and political science. Happy Sunday! This is my weekly email where I write about politics using data and share links to what I’ve been reading and writing.

Thoughts? Drop me a line (or just respond to this email). Like what you’re reading? Tap the ❤️ below the title and share with your friends! If you want more content, I publish subscriber-only posts 1-2x a week.

Editor’s note

In my pursuit to give a more personal touch to this newsletter, I’m re-instating the editor’s note at the top of the weekly post. It won’t be as formulaic this time. I hope it frames the newsletter well, and that it also makes this email a bit more relatable. Here goes.

Social distancing has begun to take its toll. Not because I crave socialization with other people—my fiancée and cats have been great company over the last two weeks—but because I desperately need daily routines and delineations between the workweek and the weekend. In the absence of a commute to work, it is hard to know when the workday stops and when playtime begins. It is harder when “playtime” typically means going out to a movie, dinner or a bar as it does for me. Weekdays and weekends blend together. Isolation is tough for me because my brain never shuts off.

So this week I’m making a conscious effort to not write about electoral politics, the usual subject of this email. Instead, I’m going to discuss a particularly crappy analysis of covid-19 I saw yesterday. It serves as a good example of echo chambering for the conspiratorial right and lets us talk about what the data actually say about the pandemic.

Actually, data show fairly worrying trends about the US coronavirus response

The virus will continue to spread without serious control measures

Yesterday, a particularly atrocious article about the coronavirus popped up on my Twitter timeline. It was a piece on Medium penned by a certain Aaron Ginn, who I can only describe as a conservative campaign staffer-turned-growth hacker/tech bro with no experience analyzing data on pandemics (it’s unclear if he does detailed analysis on other data, either). Given these facts, one would normally discount his work, but instead, the post went viral online and was embraced particularly strongly by conservative media. Several Fox News hosts shared Ginn’s post and, according to him, it got 26 million views in 24 hours (woah).

That’s not surprising in and of itself. The information ecosystem on the right has been down-playing the virus since January. Their predisposition to treat anything that reflects poorly on President Trump as a hoax or Democratic/media hysteria has led to very real differences in how their viewers are thinking about the pandemic. I’ve written about how Republicans are less likely to wear face masks or change travel plans, for example, but last week we also got survey data that show Fox News viewers think the virus is less severe than any other segment of news viewers/readers/listeners:

Ginn’s “Evidence over hysteria — COVID-19” has now been taken off Medium and even flagged by Twitter for its misleading content (you can read the archived version here). In it, he makes some particularly dubious claims, writing that we shouldn’t be concerned about the virus because it’s “only” spreading at the rate as it is in Europe; that the virus follows a bell curve and will eventually subside, as it has in China and South Korea; that there are few cases per-capita in America; and that the economic costs of severe isolation measures outweigh the deaths from the virus (they are “only” 2% of cases after all /s).

All of these points are wrong, for obvious reasons. I don’t mean this post to be a dunk-on-Aaron-fest, but it’s worth discussing the article’s shortcomings as a way to really get the facts out on the table.

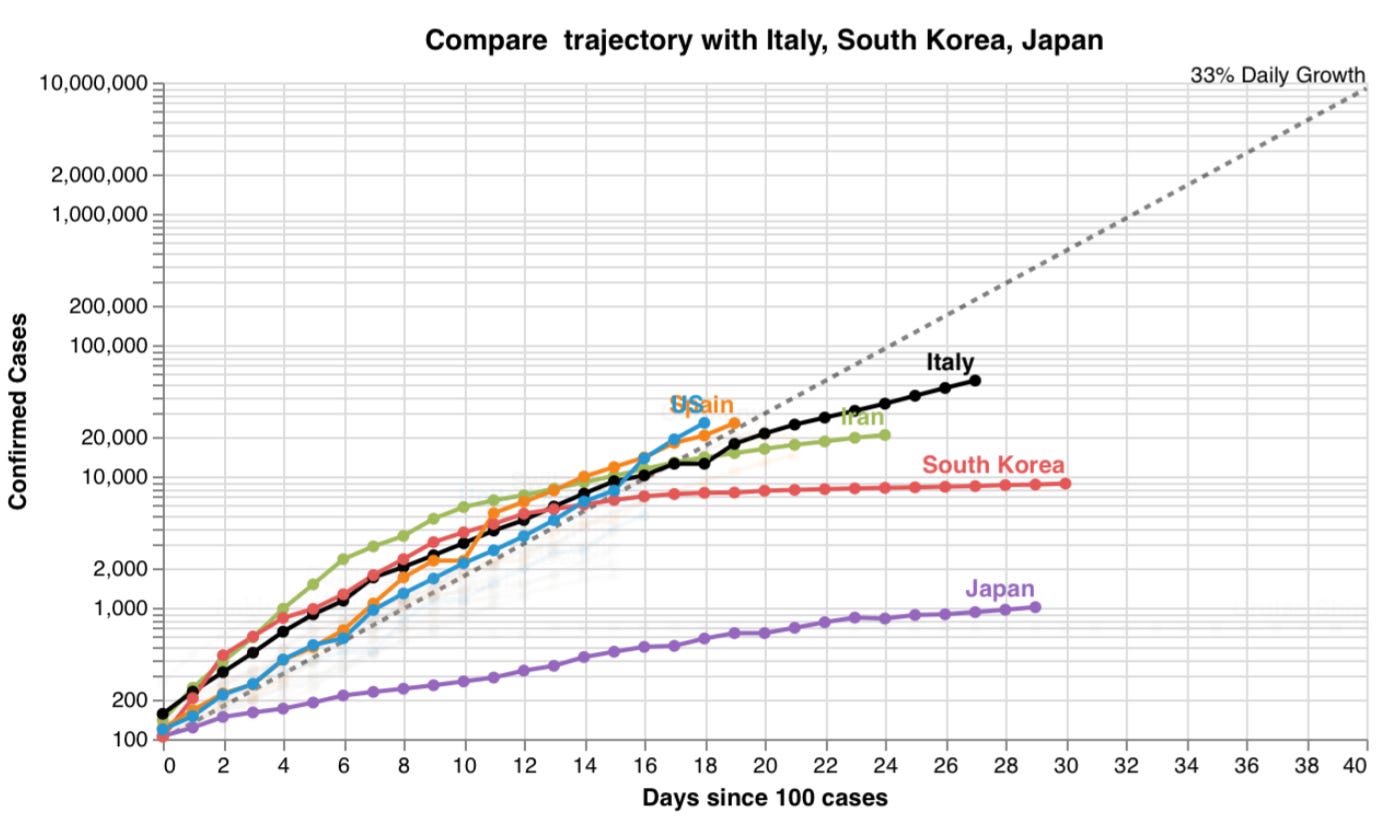

First, even if the virus continues to spread as it has in, say, Italy, then the US’s health care system will soon be overwhelmed by hospitalized cases. But cases might actually be spreading quicker here than elsewhere, according to an analysis of the latest data from John Hopkins (the US is in blue):

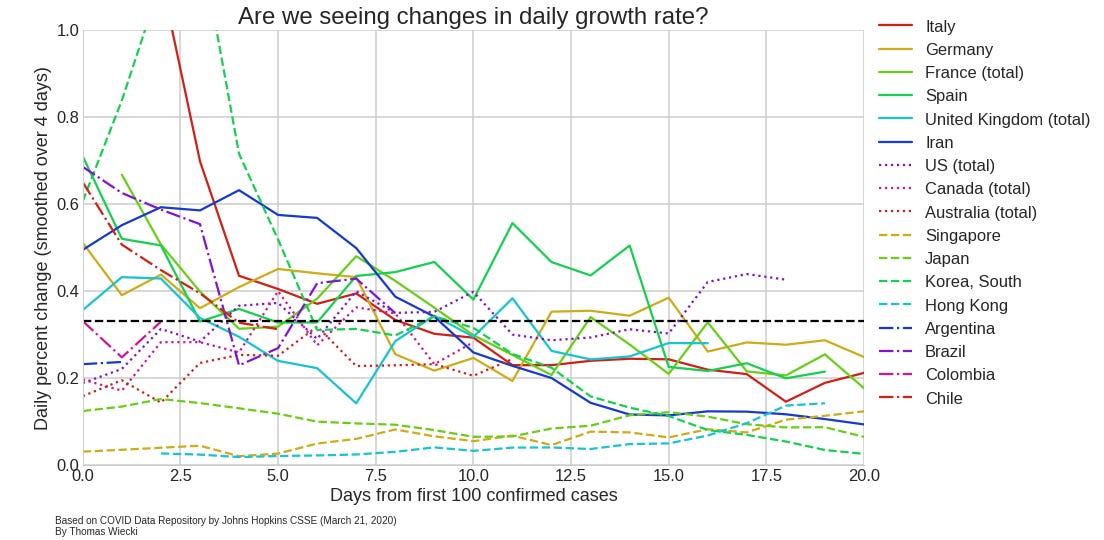

The growth rate in the United States hasn’t followed the patterns in other countries, either; it’s higher here than predictions based on how long the virus has been present in the country. At this point in the outbreak, isolation usually slows the spread of infection; we’re not seeing such a slowdown. Perhaps this is partially due to increased testing in recent days, but the growth in cases should not be entirely attributed to this.

Second, as for Ginn’s assertion that the virus will eventually slow because outbreaks follow a bell curve (the implication being, hey, let’s just let it run its course), I have to concede that it’s true that outbreaks do tend to wear down over time, as more people die and others recover. But his implication here is asinine. If the rate of the virus does not slow, the US health care system could reach capacity in a matter of weeks—and many people don’t even live in counties with nearby intensive care facilities. As was the case in Italy, we are facing an outbreak that will be worse in some regions than others, so we should also note that disparities in access of care and severity of cases could mean that some areas are overwhelmed while others aren’t.

Ginn also says that we should be focusing on per-capita rates of infection. This is a perfect case in not talking about something in which you don’t have domain knowledge. The reason that epidemiologists focus on raw numbers is precisely because health care capacity does not scale 1:1 with population. What matters is how many people the US can treat, not that there are only X cases per 100,000 people.

And here’s where Ginn’s main point comes in. Don’t the economic impacts of flattening the curve outweigh the public health crisis? Closing schools reduces GDP by a whole 0.3%! GDP could sink by 8% over 2 months if we close down restaurants, bars and sports facilities! And what about the jobs at the local diner? Why should we give in to all this draconian government regulation and spend the vast majority of the next few months sitting in our living rooms?

I think the simple answer is no; an economic contraction is not a more serious threat than the societal and personal costs of millions of preventable deaths (the CDC’s worst-case estimates right now, and the ones we would probably see if we went back to business/life-as-usual). Even the premise that economic growth matters as much or more than the excruciating toll of loss of human life comes from such an obtuse and imperceptive position of privilege that it’s easy to know beforehand that Ginn’s analysis will miss even the simplest of points about the role the government plays in responding to the virus.

But more concerning to me than Ginn’s fetishization of growth capitalism is that millions of other people have apparently also decided that the economic price of a pandemic is worth more thought and public policy than the human costs. A reasonable analyst would look at the data on covid and conclude that severe isolation measures are exceedingly necessary, then underscore the social costs we will all have to pay in order to minimize those costs. Instead, the brand of conservative data bro that Ginn represents sees only falling profits and shuttered businesses.

The data, when not massaged to make ideological points about government overreach or market dips actually tell a pretty clear and compelling story:

The virus spreads quickly, especially without social isolation and widespread testing

The virus kills people, especially when the number of infections exceeds the number of hospital beds

And I think that’s all that needs to be said. Stay home. Listen to your local health authorities. Don’t risk your life because some Silicon Valley tech bro read 5 articles about the coronavirus and wrote that “um, ackshually, the virus ain’t so bad.”

Here’s some more criticism of Ginn’s piece from an actual biologist, if you’re interested:

Posts for subscribers

Links and Other Stuff

A bunch of other data-driven analyses about the coronavirus

South Korea has 12.3 hospital beds per 1,000 people. The US has 2.8

Many Britons are not taking social distancing for covid-19 seriously

Foot traffic has fallen sharply in cities with big coronavirus outbreaks

Instagram may offer clues about the spread of the new coronavirus

Coronavirus tracked: the latest figures as the pandemic spreads

Why political-economy (or “fundamentals”) models might misdiagnose the impacts of the coronavirus

In times of market crashes and economic fallout, media outlets often turn to political scientists and election forecasters to ask: how will this shape the election?

I don’t think we can actually provide good answers to these questions. The often-cited political science forecasting models contain quite a bit of uncertainty that their creators don’t acknowledge. This means that the range of outcomes they promise are quite a bit smaller than they are in reality and that they are likelier to be “more wrong” than they say.

This is fundamentally a modeling issue. Most of the extra uncertainty comes from the fact that the margins of error from the popular models are based on how well the models fit previous data, not from how well they predict results they haven’t “seen” yet. Obviously, predicting the outcome of November’s election is more in line with the latter definition of error than the former, and so-called “out-of-sample” errors are much larger for these models (I know because I’m building several of them right now).

Extra error comes from the fact that the models don’t take into account that the economy is less a driver of vote choice now than it was in the past. A model trained on the relationship between GDP growth and the incumbent’s vote share, for example, will produce the average coefficient for growth across election from the 1970s (or whatever the starting point) to 2016, which will overshoot the variable’s importance now and undershoot it earlier.

The market has crashed and the economy has already entered a recession, but president Trump’s approval rating hasn’t budged. Maybe it will take a dip by the time we get to the summer (when these models typically make their official predictions), but even then, the models don’t answer the question of whether people are punishing the president for their flailing 401ks (so far, they aren’t).

I wouldn’t put too much stock in these traditional “fundamentals”-based election forecasting models, especially right now. More to come later.

What I'm Reading and Working On

I wrote for The Economist last week about why the age divide in the Democratic primary isn’t all that concerning, electorally speaking. Young Democrats don’t like Joe Biden, but the vast majority are going to vote for him anyway once we get November. But from a party/coalition perspective, the bigwigs have a lot of reckoning and soul-searching to do to figure out how to get young people to believe and take part in the process.

I’m preparing a few charts on the stock market for next week. I’m also thinking about new ways to extract insights from data about the covid-19 pandemic. That is, of course, extremely hard to do…

Thanks for reading!

Thanks for reading. I’ll be back in your inbox next Sunday. In the meantime, follow me online or reach out via email if you’d like to engage. I’d love to hear from you!

If you want more content, I publish subscribers-only posts on Substack 1-3 times each week. Sign up today for $5/month (or $50/year) by clicking on the following button. Even if you don't want the extra posts, the funds go toward supporting the time spent writing this free, weekly letter. Your support makes this all possible!