A slim Republican House vote, what it means to be a "moderate," and the church class divide | Links for December 11-17, 2022

Was 2022 really a "decent year" for Republicans?

Happy Saturday, subscribers, and here are your weekend links:

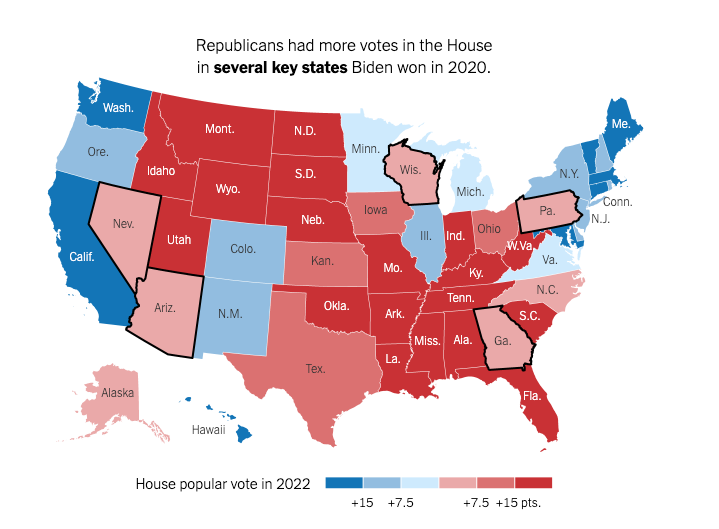

1. The New York Times maps our Republicans’ popular vote “win”

A newsletter from Nate Cohn this week details the geography of the Republican Party’s popular vote victory in the House of Representatives this November. The current tally shows they beat Democrats by about 3 percentage points — 51 percent to 48 percent — or by about 1.6 points if you predict what would have happened in uncontested seats (which you should do). For context, that makes for about a 4 point swing in the (imputed) national popular vote for the House relative to 2020, about half what you get in the average midterm since 1940.

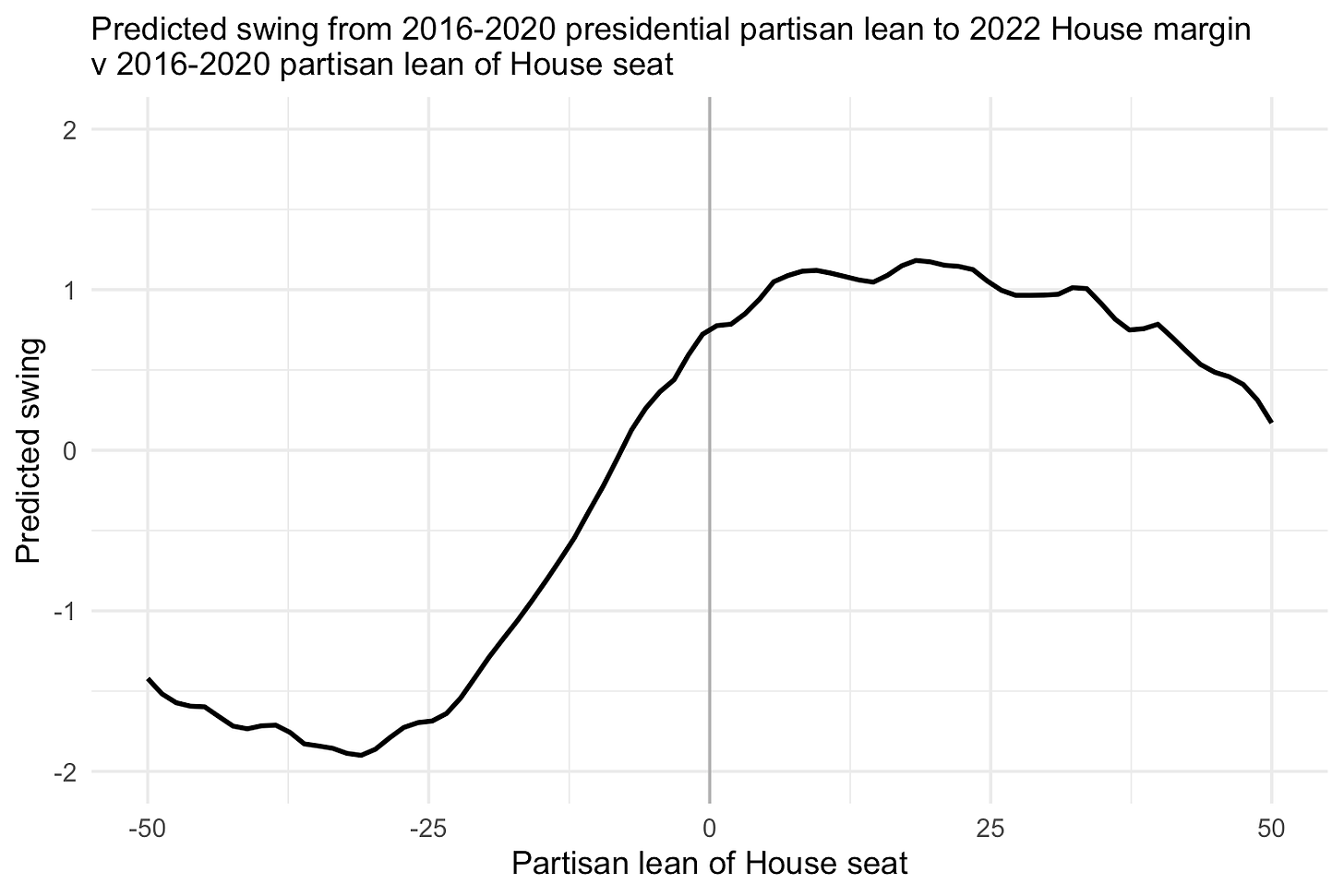

Cohn makes the point that this swing should have resulted in Republicans winning close to 230 House seats, yet they won only 223. And so the mystery: Why? The answer, as I have explained, is that the swing in the popular came disproportionately in uncompetitive seats. Take a look at the map of statewide changes in vote totals per Cohn:

and by House district here:

However, Cohn notes, there remains a pattern of“Real Republican Strength” in the results if you look at it a different way:

Republicans outran Donald J. Trump’s 2020 showing in nearly every state. The exceptions are all very small states with one or two districts, where individual races can be unrepresentative of the broader national picture.

Under a lot of circumstances, this Republican showing would be impressive. Consider, for instance, that Republican candidates won the most votes for U.S. House in all four of the crucial Senate states where Republicans fell short: Pennsylvania, Arizona, Georgia and Nevada.

Or, put differently: Republicans would have won the Senate, and fairly decisively, if only the likes of Dr. Mehmet Oz or Herschel Walker had fared as well as Republican House candidates on the same ballot.

Republicans also won the most votes in Wisconsin, another state President Biden won in 2020. If this were a presidential election, House Republicans would have claimed 297 electoral votes. This doesn’t necessarily mean anything for 2024; it’s just another illustration that equivalent Republican strength could have looked quite impressive under slightly different circumstances.

Although the data is still fragmentary, it is clear that the Republican popular vote win was backed by a fairly sizable turnout advantage. These figures are all generally consistent with a decent Republican year, like the one evident in the state and national House popular vote.

It just didn’t show up on the scoreboard.

This is mostly a good analysis, but I don’t find the translation to electoral college votes particularly helpful. In fact, it is obfuscating the narrative in a significant way.

Cohn’s whole point is that House Republicans managed to do better than Senate GOP candidates, on average, because (a) of a large turnout advantage, mostly in crimson red seats; and (b) because of the double whammy of good Democratic nominees and ideological extremism of Republican recruits in those Senate races. He gives us this graph:

But if the 2024 election were happening today, we would likely have a Republican nominee closer to the average of Senate candidates not Republican ones. So is the aggregate of House maps really all that predictive? No, he admits; But is it informative? No, I say. In 2018 Democrats won the House popular vote by 8 percentage points. That was not illustrative of their national advantage heading into the 2020 election (which may have even been negative at the beginning of the year, before covid-19).

Cohn says:

The national and state House popular votes lead me to adopt the “decent Republican year” frame. But there are just enough examples of unexplained Democratic resilience that I wouldn’t be too put off if someone preferred the framing the other way.

I don’t see it that way. Here’s why:

Republicans won the House popular vote by 1.5 percentage points. That is a below-average swing.

Republicans picked up just 10 seats in the House. That is a below-average swing.

Candidates endorsed by Trump or who endorsed his “big lie” conspiracy theories about elections and democracy did particularly poorly. If Republicans did well, only a subset of them did so — and in spite of the leader of the party, not because of him.

2. Can these people just tell us what they mean by “moderate,” please?

Ruy Teixeira, the liberal pundit recruited earlier this year away from the Center for American Progress to the conservative American Enterprise Institute for a gig pushing Democrats to the center on social issues, has published a list of “Ten Reasons Why Democrats Should Become More Moderate”.

Some of them include:

1. In the 2022 election, the reason why Democrats did relatively well was support from independents and Republican leaning or supporting crossover voters—not base voters mobilized by progressivism. These independents and crossover voters were motivated to support Democrats where they did because many Democrats in key races were perceived as being more moderate than their extremist Republican opponents. Moderation = Democratic votes.

and

2. In fact, as the Democratic party has moved to the left over the last four years, they have actually done worse among their base voters. They’ve lost a good chunk of their support among nonwhite voters, especially Hispanics, and among young voters. Since 2018, Democratic support is down 18 margin points among young (18-29 year old) voters, 20 points among nonwhites and 23 points among nonwhite working class (noncollege) voters. These voters are overwhelmingly moderate to conservative in orientation and they’re just not buying what the Democrats are selling. Moderation = Democratic votes.

But I don’t find the post particularly helpful. For one thing, Democrats’ losses among nonwhites are fueled predominantly by ideological and social sorting (by his own admission). Democrats cannot appeal to these votes by taking more moderate stances on issues. That’s because they would still have their identities as liberal Democrats — so “Moderation = Democratic votes” among conservative Latinos does not strike me as a high-value proposition.

But as always, when I hear people talk about this, I’m wondering what exactly Democrats are supposed to be moderating on. Take the first point: Did the Democrats do well with Independents because they moderated on, say, abortion or democracy this year? On the economy? They did not yield to the GOP on access to reproductive care, last time I checked. In fact this year, if anything, shows the costs of Republicans moving to the extremes and Democrats holding the line. I’m just not convinced.

So maybe here’s something. Teixeira writes:

According to polling this year by JL Partners, just 10 percent of Trump-Biden voters think we need to go farther on political correctness in society today, compared to 51 percent who think we’ve gone too far. The analogous numbers for teaching children about trans issues are 14 percent (go farther) and 36 percent (too far); for efforts to remove historical statues, 8 percent (go farther) and 62 percent (too far); for teaching children about critical race theory, 18 percent (go farther) and 34 percent (too far); for removal of people from jobs for past offensive comments, 12 percent (go farther) and 43 percent (too far); for Black Lives Matter protests, 10 percent (go farther) and 49 percent (too far); and for use of different gender pronouns, 10 percent (go farther) and 51 percent (too far). Since progressives want to press the accelerator on all these things, their approach doesn’t seem like a good fit for this important swing voter group—and really probably for any swing voter group. Moderation = Democratic votes.

Aha. Except, these are not wedge issues to voters And, again, I don’t think any prominent Democrats campaigned against political correctness this year. And yet, as he says, Democrats won Independents!

I think the story is a little more complicated.

3. There’s a Growing Class Divide in Church Attendance

Such is the title of a data-rich blog post by Daniel Cox, who runs the Survey Center on American Life. There’s a lot in the post that you should read, but here is the money chart:

This actually struck me quite a bit. The story we’re told about religiosity in America is that our secular education system is dismantling institutions of faith. But that does not seem to be the case!

The reasons why are a bit complicated but super interesting. Cox shows us it has to do with how Boomers raised their kids. College-educated Boomers prioritized religion more than non-college-educated Boomers:

I find puzzles like this fascinating. Churches are one of the few organizations left that weave together the fabric of our social lives. Religious institutions, while instruments of incredible harm in some cases, also hold a unique power to increase earnings and social capital for people who otherwise have little access to richer and better-connected social groups. And yet, today in America, it is the better-off who have access to those groups!

Hmmm. I wonder whether the cost of belonging to a congregation is a factor. I also wonder whether authoritarian congregations lost more attendance than Episcopal churches, for an example, or liberal synagogues, for another example.