Welcome! I’m G. Elliott Morris, a data journalist at The Economist and blogger of polls, elections, and political science. Happy Sunday! This is my weekly email where I write about politics using data and share links to what I’ve been reading and writing.

Thoughts? Drop me a line (or just respond to this email). Like what you’re reading? Tap the ❤️ below the title and share with your friends! If you want more content, I publish subscriber-only posts 1-2x a week.

Dear reader,

My brain is just mush right now. Somehow it is impossible to get anything done during this pandemic, yet I also am being more productive than ever. There’s this old law (actually, it’s a theory) about how work expands to fill the time we allot for it. That definitely seems true during the coronavirus quarantine, at least on my end.

My mess of a brain has still produced one coherent take today, however. Something has been bugging me about economic-voting models recently that I’d like to at least get on paper (er, screen?) here. This is a complex subject that I won’t be unpacking in its entirety tonight. Let me just add one note to the ongoing conversation over how well political science models can anticipate the political fallout of recessions (and, honestly right now, depressions). I have limited data, but we can at least start thinking through the problem.

Remember to take care of yourself right now. I heard from a lot of y’all after last week’s email about how you’re enjoying these dispatches from isolation. I would love to hear from more of you—the more emails the merrier.

A note on voting and the economy

How much will the recession matter to voters?

Honestly, I’m running out of ways to characterize just how bad the economy is right now. According to several economists’ estimates, the unemployment rate has soared past 10% and might be approaching 20. Jobless claims over the past 3 weeks have surpassed 16 million. It’s safe to say that this is the worst economy since the Great Depression. It’s worse than after the 1981-83 contraction. It’s worse than the 07-08 fiscal crisis and subequent recession. Over the next few months, more Americans will be without the means to make rent or put food on the table than at any time in the past 80 years.

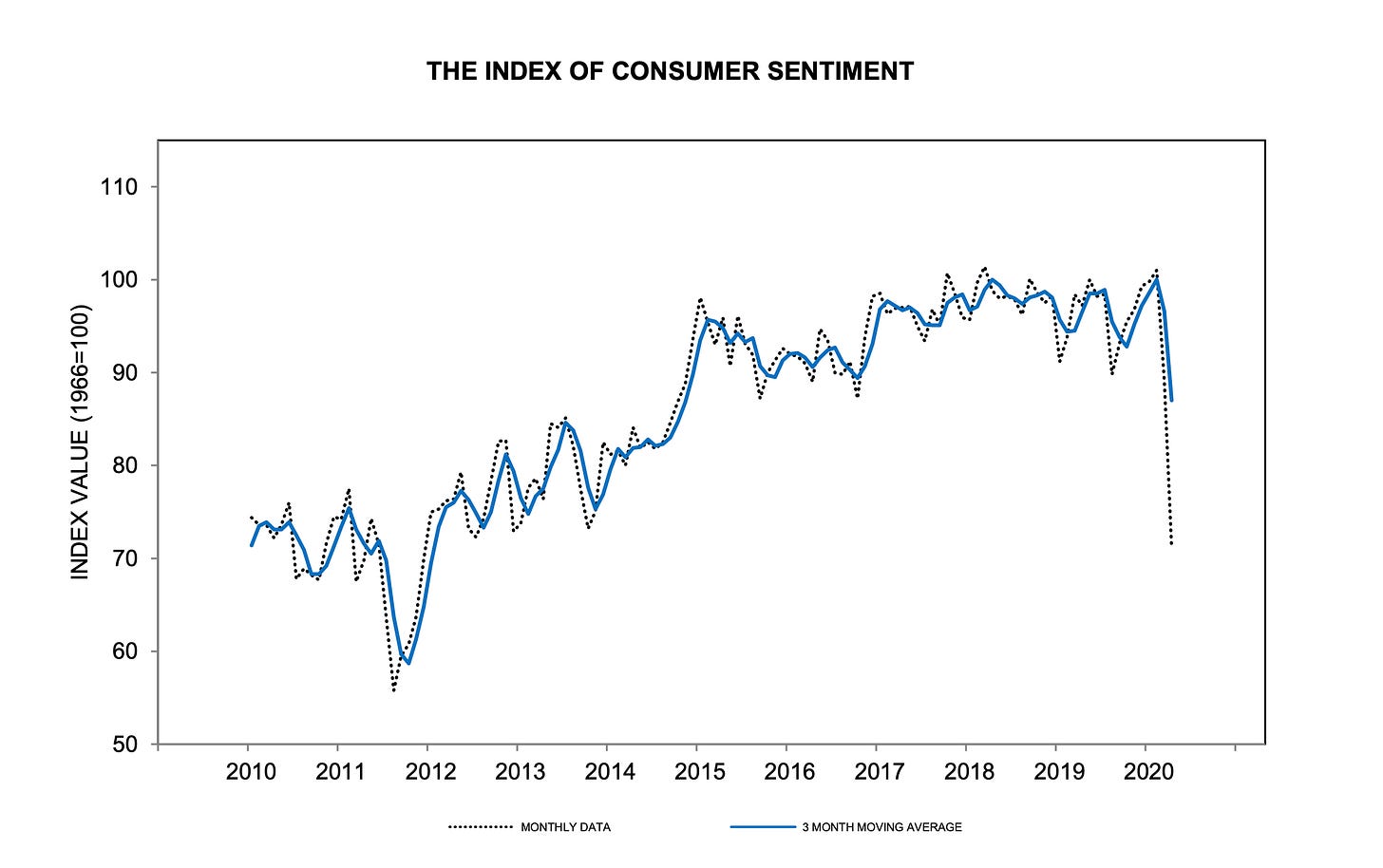

This is a catastrophic crisis. Its toll on the American people is already evident. The University of Michigan’s surveys of consumers find that we’re more pessimistic about growth than at any time over the past decade:

And check out these alarming pictures of people waiting in line at the San Antonio food bank, where a record-setting 10,000 households asked for help last week:

Politically, this has made for an increasingly nervous and paranoid president Trump. Just six weeks ago his re-election campaign was focused on an “amazing economic machine” that had delivered unparalleled economic gains (actually, the economy has been quite middling over the past 3 years, at least in the historical contest). Now, the president avoids the subject like the plague (except when he’s cheering on 1-day, fleeting increases in the Dow).

We would infer from these trends that voters’ evaluations of Mr Trump have turned sour. We might also think that his re-election numbers have sunk. In fact, neither has budged. Trump’s approval rating currently stands at 44% according to FiveThirtyEight’s polling aggregate and Joe Biden is running about 6 points ahead of him in general election matchups, just about where he has been for the past couple of months.

This is all a bit confusing, right? Political science tells us that a bad economy reflects poorly on the incumbent president. The 1980 and 2008 elections were historic blows for the party controlling the White House. Yet the economy has turned south but Trump’s numbers haven’t changed.

Granted, it might be too early for people to have really factored in the recession in their voting calculations. And it is early in the election year, too; people may not have really tuned in yet.

But here’s another possibility: It could very well be the case that the decoupling in economic sentiment and presidential approval that we’ve observed during the past decade’s economic expansion will also hold true during a contraction, or even a severe recession. If that’s the case, we shouldn’t expect the “fundamentals” models of elections to “work” in predicting the outcome of the November election. Thanks to partisan polarization, whatever negative effect the recession would normally have on Mr Trump’s vote share wouldn’t materialize. He would match his approval rating in the polls (and, accordingly, probably lose the election, but not as severely as the economy today predicts).

But this is all conjecture, at least for now. We should know more after we have a few more weeks (or months?) of data. In the meantime, I wouldn’t put too much stock in forecasts that don’t factor in current trial-heat polls. They will probably overestimate support for Joe Biden—just like 3 months ago, when the economy as humming, they were likely overshooting Donald Trump.

Posts for subscribers

April 8: Joe Biden starts the 2020 general election as the clear favorite. Joe Biden is currently running ahead of Donald Trump nationally and in key states, but he is not guaranteed a victory

Thanks for reading!

Thanks for reading. I’ll be back in your inbox next Sunday. In the meantime, follow me online or reach out via email if you’d like to engage. I’d love to hear from you!

If you want more content, I publish subscribers-only posts on Substack 1-3 times each week. Sign up today for $5/month (or $50/year) by clicking on the following button. Even if you don't want the extra posts, the funds go toward supporting the time spent writing this free, weekly letter. Your support makes this all possible!