A new study shows how polarization alone is not responsible for the surge in willingness to commit partisan violence

The researches also found that correcting misperceptions of the opposition party’s low support for democracy didn’t decrease illiberal attitudes

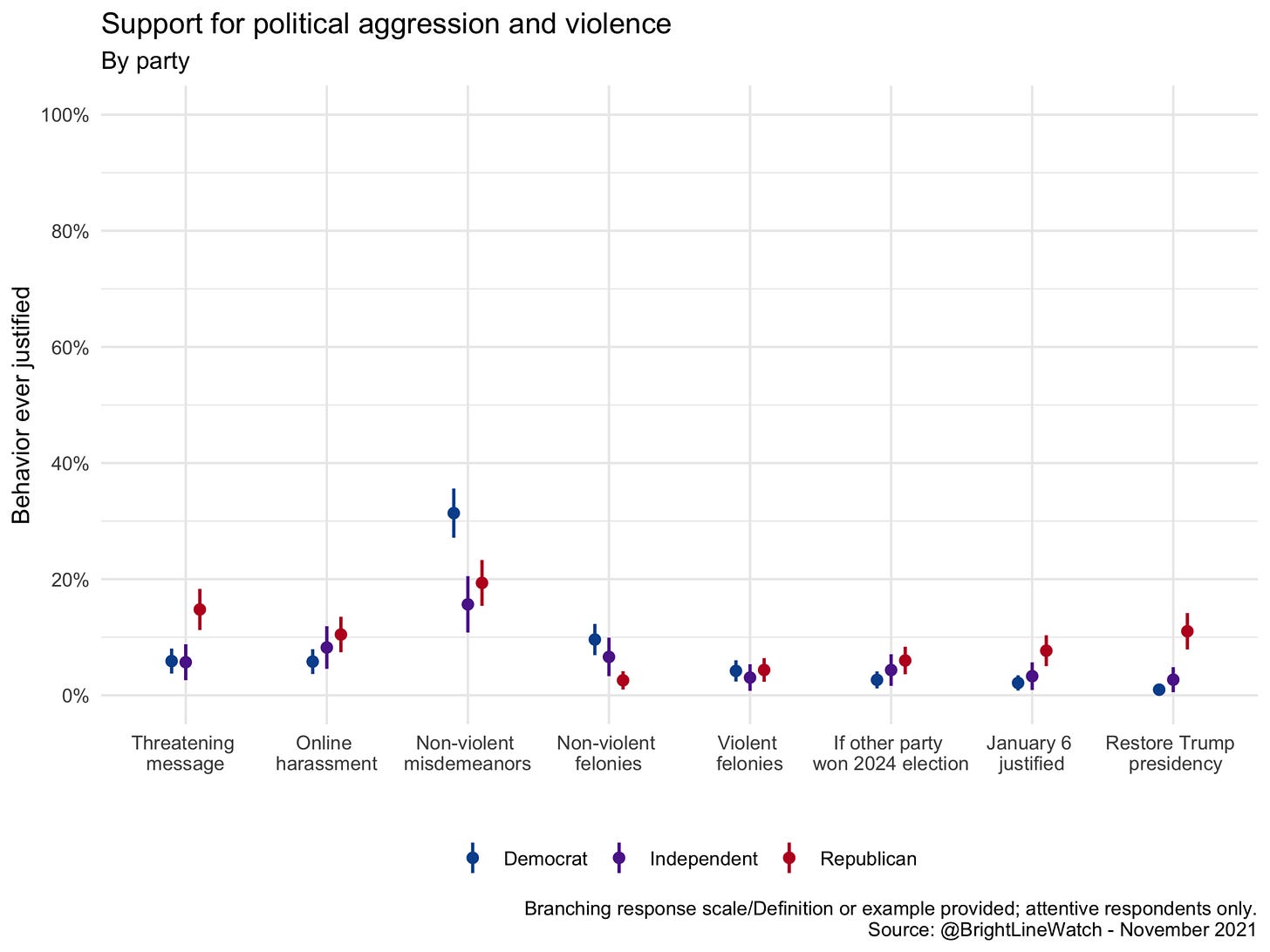

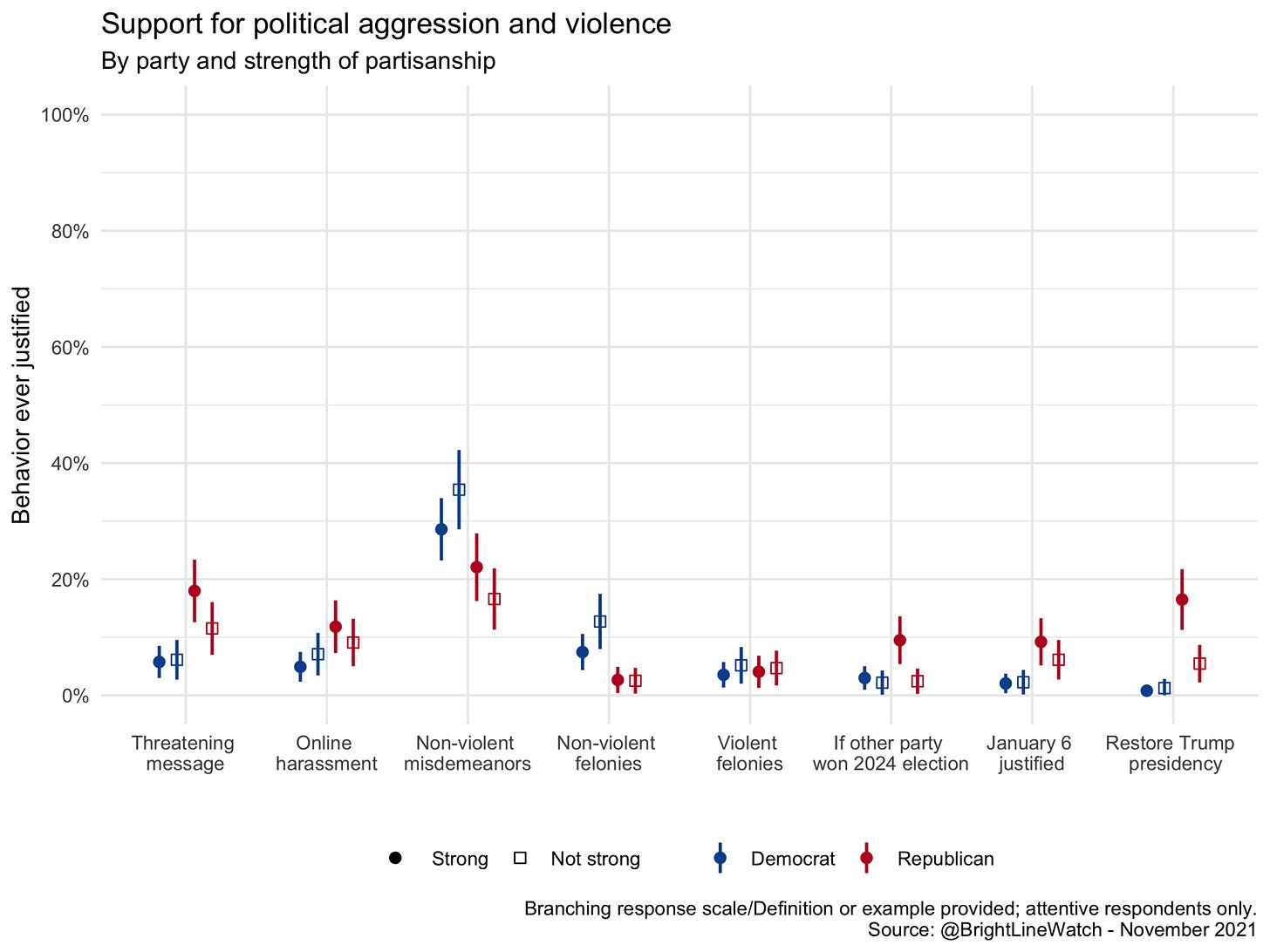

Roughly one out of every ten Republicans would support using violence to reinstate Donald Trump as president, a new study from Bright Line Watch (a watchdog research group made up of political scientists) reported this week. One in every six “strong Republicans” said the same.

Here are the charts from their report. They also show higher GOP support for other types of violence or aggression. Democrats are much more likely to say non-violent misdemeanors and felonies can be justified as political means.

Though not a new finding, this is nevertheless alarming. The attempted coup on January 6th — perpetrated by what now looks like an organized faction of GOP executive leadership and key legislators — illustrates how even small currents of extremism among the mass populace can have violent consequences. It takes only a small percentage of people to start a revolution.

But what I’m more interested in is what the report can tell us about potential solutions. I find two things in the report worth emphasizing.

Polarization is not the major cause of illiberalism on the right

The first notable bits are the results of a survey experiment designed to correct misperceptions of partisan support for political violence and test whether doing so decreases one’s own tolerance for aggression, norm-breaking, and what-have-you. The hypothesis here is that the tendency for voters of one party to overestimate how likely members of the other party are to support violence &c would increase their own support for similar norm violations. That makes a good amount of sense, right? Especially in a two-party system where decisions are polarized and high-stakes, you’d expect people to respond in a reactionary way towards escalations of a zero-sum game.

Except that’s not what the report found. Well, not in a substantial way. But to get there, I need to explain how the experiment worked.

First, the authors asked a random subset of respondents to guess the percentage of co-partisans and out-partisans that would say that each of the following principles is important to democratic government:

Government agencies are not used to monitor, attack, or punish political opponents

Elections are conducted, ballots counted, and winners determined without pervasive fraud or manipulation

Law enforcement investigations of public officials or their associates are free from political influence or interference

All adult citizens enjoy the same legal and political rights

As expected, the questions revealed that people estimate that their co-partisans (eg, Democrats if you’re a Democrat) are much more supportive of key democratic values than out-partisans (in this case, Republicans). The gaps between estimates for the in- and out-party group range between 10 and 30 percentage points depending on the question.

The randomly-selected respondents were then given accurate information about how the out-group actually felt about those norms (the correct percentages were taken from an earlier Bright Line Survey). Then, the full sample was asked whether they supported different types of anti-democratic actions, including whether their co-partisans should….

… do everything they can to hurt the [other party], even if it is at the short-term expense of the country;

… do everything in their power within the law to make it as difficult as possible for [the other party] to run the government effectively;

… redraw districts to maximize their potential to win more seats in federal elections, even if it may be technically illegal;

… use the Federal Communications Commission to heavily restrict or shut down Fox News [shown to Democrats] / MSNBC [shown to Republicans] to stop the spread of fake news

And, finally: that it’s OK to sacrifice US economic prosperity in the short-term in order to hurt [the other party’s] chances in future elections.

By exposing only half of the sample to the questions and correct information about co- and out-partisans’ support for democracy before asking about actions that curtail it, the researchers are able to assess to what extent that “treatment” (correcting misperceptions) reduces anti-democracy sentiment. They found only minor differences between the treatment and control groups. Here is the chart of their results:

And the authors write:

Across the full battery of anti-democratic actions, the effect of the experimental treatment was statistically significant and in the expected direction, but substantively small (just 0.08 standard deviations). Providing accurate information about support for democracy among partisan adversaries reduced support for illiberal actions by co-partisans by 0.07 points on a five-point agree-disagree scale. (Full results are shown in the appendix.) We specifically observed significant, but small, reductions in support for actions intended to damage the other party (hurt the other party at the expense of the country, make it hard for them to govern, and sacrifice economic prosperity to damage them). By contrast, the intervention had no measurable effect on actions against unfavorable media sources or gerrymandering.

These results suggest that underscoring the opposition party’s shared commitment to respecting democratic norms might help strengthen opposition to illiberal actions by co-partisans, but any such effects would be quite limited in magnitude.

. . .

These conclusions are very important for reformers to internalize. They suggest that ideological polarization and the strength of partisans’ identities are not the main drivers of support for anti-democratic and illiberal actions.

So what is?

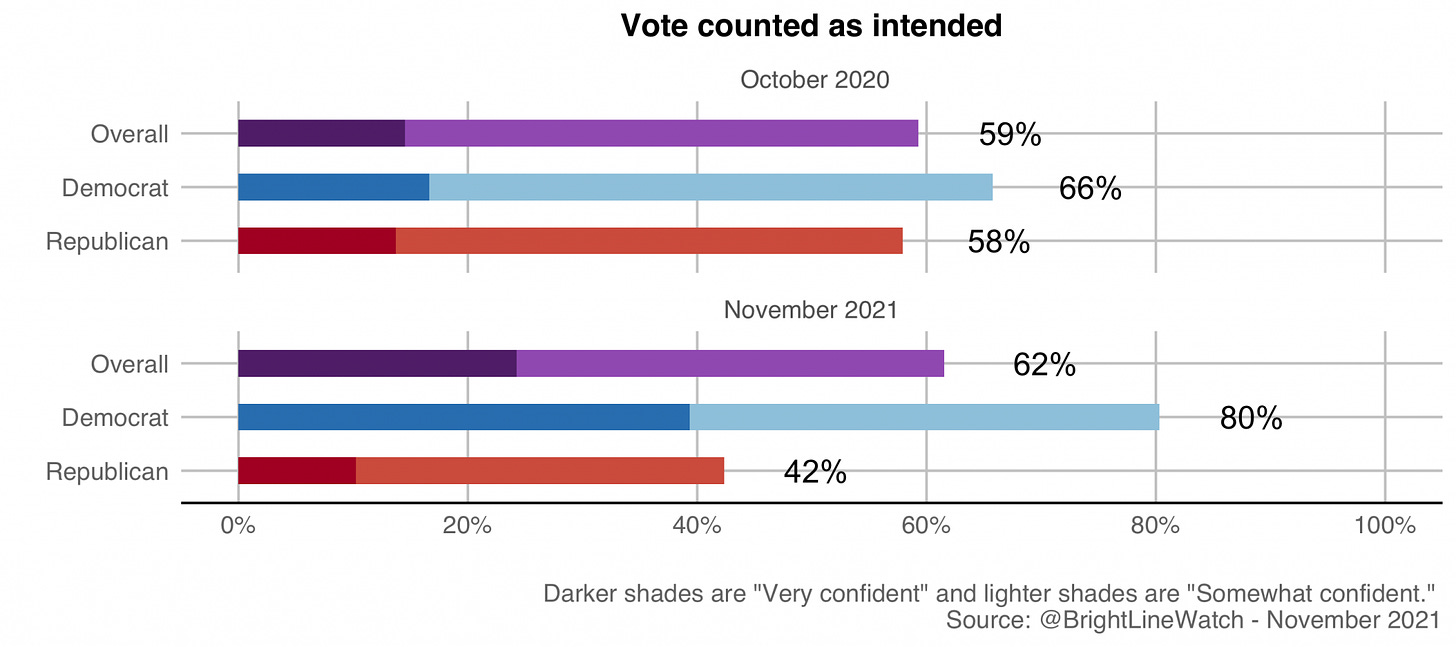

The main theory among political scientists is that support for illiberalism among the mass public comes from political elites who they like and identity with, and who also happen to espouse these ideas. There are certainly enough political science articles mentioning ‘opinion leaders’ and ‘elite opinion leadership’ or ‘partisan heuristics’ for this case to be believable. And one anecdote about illiberalism after 2020, in particular, is that Republicans were relatively trusting that the outcome of the election would be legitimate until Democrats won and Donald Trump started his campaign against the validity of their votes. People experience motivated reasoning to adopt party positions, even when they are anti-democratic (or have no basis in fact).

To be sure, I doubt the elite-driven explanation accounts for the full rise in authoritarianism on the right over the past few years. But this is something to focus on — especially as other potential explanations are disproven.

Proposals from the wisdom of (expert) crowds

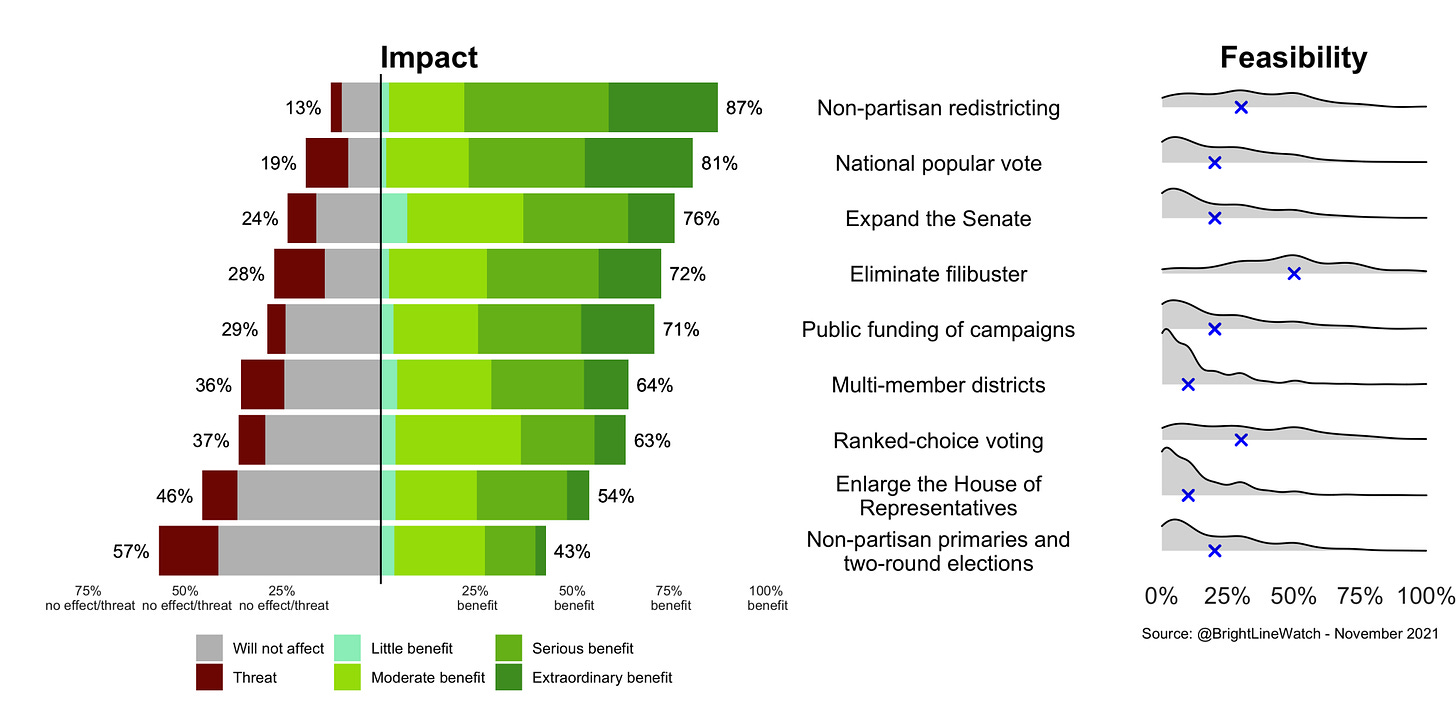

The very useful thing about the Bright Line Watch survey is that they also survey experts to solicit their opinions. And the political scientists they polled circled around a few key proposals to right the ship of state. All are pretty big changes from the status quo, and most seem unlikely.

Overall, “large majorities of experts (74%) and of the public (62%) favor a fundamental change to the structure of American government,” the report says. They continue

“Among reform supporters, a majority of experts and the public believe the best approach to making significant change is to pursue reforms that do not require amending the Constitution (45% of all experts, 33% of all members of the public). Relatively few in either group believe the best approach is to seek to amend the Constitution (22% of experts, 23% of the public) or to create a new charter altogether (7% of experts, 6% of the public). Yet, no single approach attracts majority support among either group overall.”

As for precisely what’s on the menu? The experts surveyed circled around a few things that would be the most impactful. Experts put non-partisan redistricting above everything else, with 87% of them saying partisan fairness in mapmaking would provide “little,” “moderate,” “serious,” or “extraordinary” benefit. After the, 81% favor a system for the national popular vote, 76% want to expand the Senate, and 72% want to eliminate the filibuster. The chart below lists a few other proposals to achieve proportionality in House elections and enact a system for multi-party democracy:

Note that few experts think any of these reforms are likely to happen, except eliminating the Senate filibuster — which they gave a median of 50% chance of happening. The median forecast for the other eight reform proposals was roughly 25% (national popular vote, Senate expansion, public funding of campaigns, non-partisan primaries, and two-round elections) or 10% (multi-member districts, enlarging the House of Representatives).

Those odds are not great.

What is the tipping point?

The Bright Line Watch report beings by noting that Joe Biden entered the presidency in January with the aim of strengthening American democracy, reducing divisions, and passing popular policies. A year later, they write, “he convened a democracy summit to address the challenges that rising authoritarianism poses around the world. Here at home, however, the promise of unity has faded and our democratic vulnerabilities remain.”

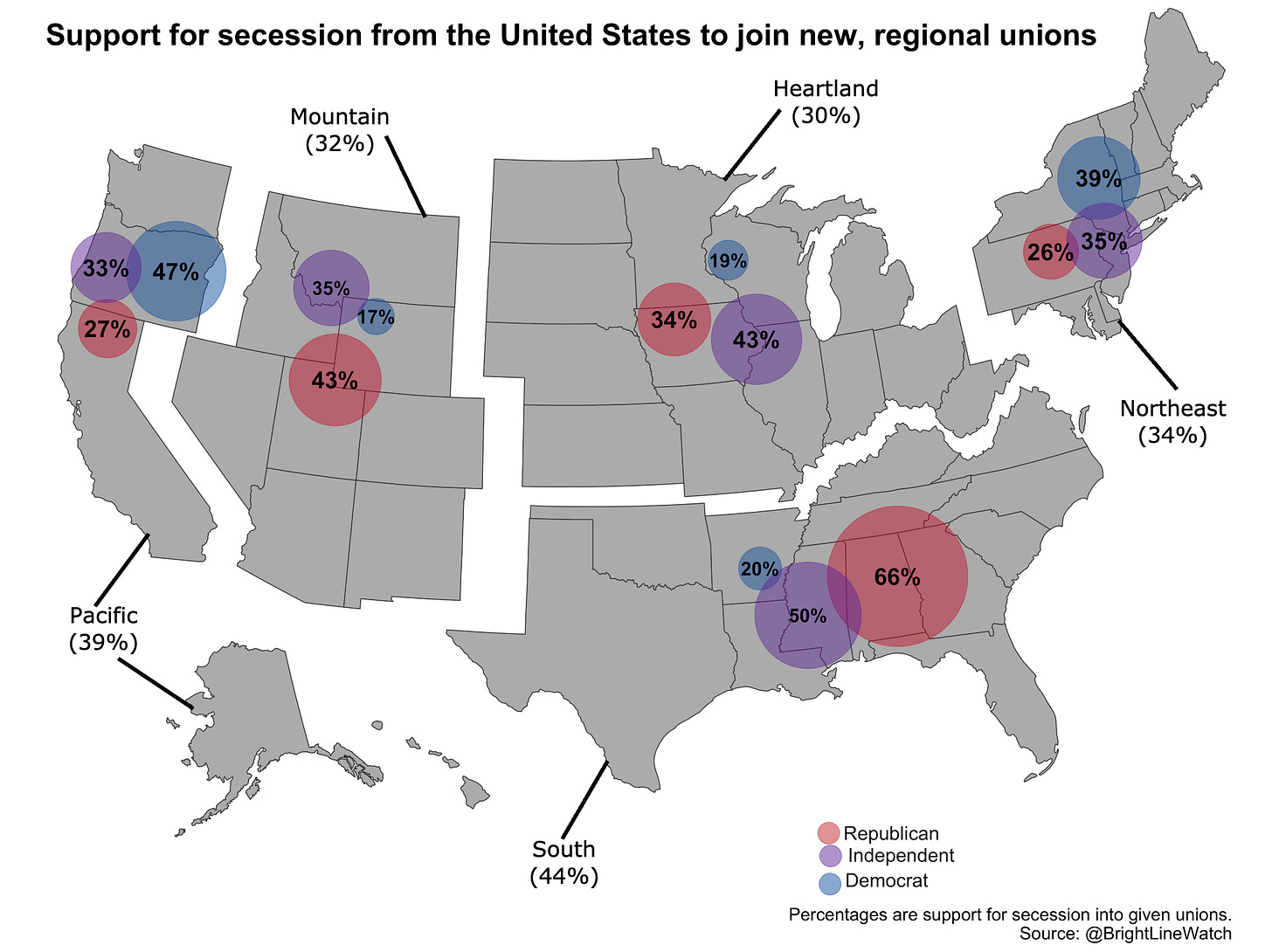

These democratic vulnerabilities span from institutional threats, which are well covered, to the wavering embrace of democratic ideals among the mass public, which pundits have tended to ignore. One thing I find missing in these discussions is a note of just how fragile our union is; or, put the opposite way, how common feelings of disunity are. And you can’t be a union without unionists. Along these lines, the last Bright Line Watch report found that support for succession was concerningly high, especially (but not exclusively!) among Republicans in the South:

These divides are not just political, but cultural and social too. More Americans than ever before in our history live completely separate lives, with little contact across the aisle and almost entirely bifurcated attitudes on the most important policy issues of our day. And while individuals from across the aisle have more in common with each other than they typically assume — as evidenced by some of the data in Bright Line’s report — we are in aggregate quite separated from each other. It makes matters all the worse that we are increasingly geographically separated, too. These geographic, cultural, and political divide combine along similar axes to make it almost inherently hard for a national government to work optimally.

. . .

To bring this back to the top, let me be clear that my position is not that I think polarization is irrelevant to this equation. On the contrary: I think our institutions set the stage for polarization, and in turn that the widening chasm between us creates the conditions for demagogues to spread electoral illiberalism in order to advantage their pursuit of political power.

But isolating the influential role of certain figures in the decline of American democracy is necessary before we can know what to do next.

Thank you — and also a programming note

I would like to thank everyone who has subscribed to this newsletter for their support. This year started out well for me — first: on book leave, and then working on some interesting new projects at my day job — but turned out to be pretty rough in the end. I think that’s due to reasons most all of us have in common: stress, anxiety, uncertainty and such. And working 100% from home is really getting burdensome. So getting to sit down twice a week and write to you has provides me with an anchor in rough waters.

Yet the waters on the horizon still looks choppy. The threats to democracy — institutionally and socio-culturally — are only growing more severe. And misperceptions about the power of data to provide insights into those threats and tell interesting stories about our lives persist. Attacks on polling are especially concerning. I am looking forward to tackling those challenges again for another year, but am not ignorant of the challenges we all face. While data-driven journalism offers both readers and writers a shortcut to objectivity, only those who are paying attention will internalize the insights.

So I hope you will stay subscribed for another year. Not only because there are few other journalists using political science and public opinion data to talk about the authoritarian currents in American politics, but also because the upcoming midterm electoral cycle will be a key test of the strength of that current. I am excited to be doing some work on handicapping it again soon. All of that will happen with the garage door open, so to speak — and this blog offers readers a seat at the workbench. If you haven’t shared this newsletter in the last couple of weeks, the holidays are a good time to send it to a friend who might subscribe.

And for programming: as Christmas is here, I am taking the next week off in order to relax and recharge with my family . But I will send a few more public missives this year in the final week that follows.

Cheers to everyone, and thanks for a successful 2021,

Elliott

Merry Christmas Elliott! I hope you have a good and safe Christmas!

-Elliot

Elliott, I used to live and work among working class rednecks. For all their good qualities, their eager delight in violence drove me away permanently. It was cultural. If you want to be a man you have to fight. Same is true of black gang kids, per the autobiographical books of many - James Baldwin's Fire Next Time, Ta-Nahesi Coates' Between The World And Me.

Speaking of books. . .