The Democrats v Manchinema and the strategic paradox of the progressive left

Many Democrats have pilloried Joe Manchin and Kyrsten Sinema in the press to try to force them left — but they may in fact be hurting themselves electorally

A long piece of mine on, roughly speaking, the future of the Democratic Party is in The Economist’s print edition this week (and online right now). It is chock-full of all the political science/demographics-y bits and bobs you all like from this newsletter, so please give it a read. (If you don’t have a subscription, you can log in with an email and read 3(?) articles for free each month.)

One of the important things that got cut from the piece was about this paradox Democrats are in with how they deal with their moderate holdouts, especially in the Senate. They have lambasted Joe Manchin and Kyrsten Sinema for not signing up to the big-spending version of Joe Biden’s Build Back Better agenda (which is mostly popular in its particular proposals with a majority of Americans).

The central problem here is that attacking Manchin (and, to a lesser extent, Sinema) for not being progressive enough or being too strict with the Congressional purse can hurt the Democrats ability to win in the places that are most favorable to people like him. But those rural areas of the heartland slso supply more Senators than they are owed based on their share of the population.

But before we get there, we must briefly review the “nationalization” of our politics. Political scientists describe nationalization as the process by which the vast majority of our local/sub-national political conversations have been subsumed by national debates over politics. Here’s how Dan Hopkins puts it in the jacket to his book The Increasingly United States:

In a campaign for state or local office these days, you’re as likely today to hear accusations that an opponent advanced Obamacare or supported Donald Trump as you are to hear about issues affecting the state or local community. This is because American political behavior has become substantially more nationalized. American voters are far more engaged with and knowledgeable about what’s happening in Washington, DC, than in similar messages whether they are in the South, the Northeast, or the Midwest. Gone are the days when all politics was local.

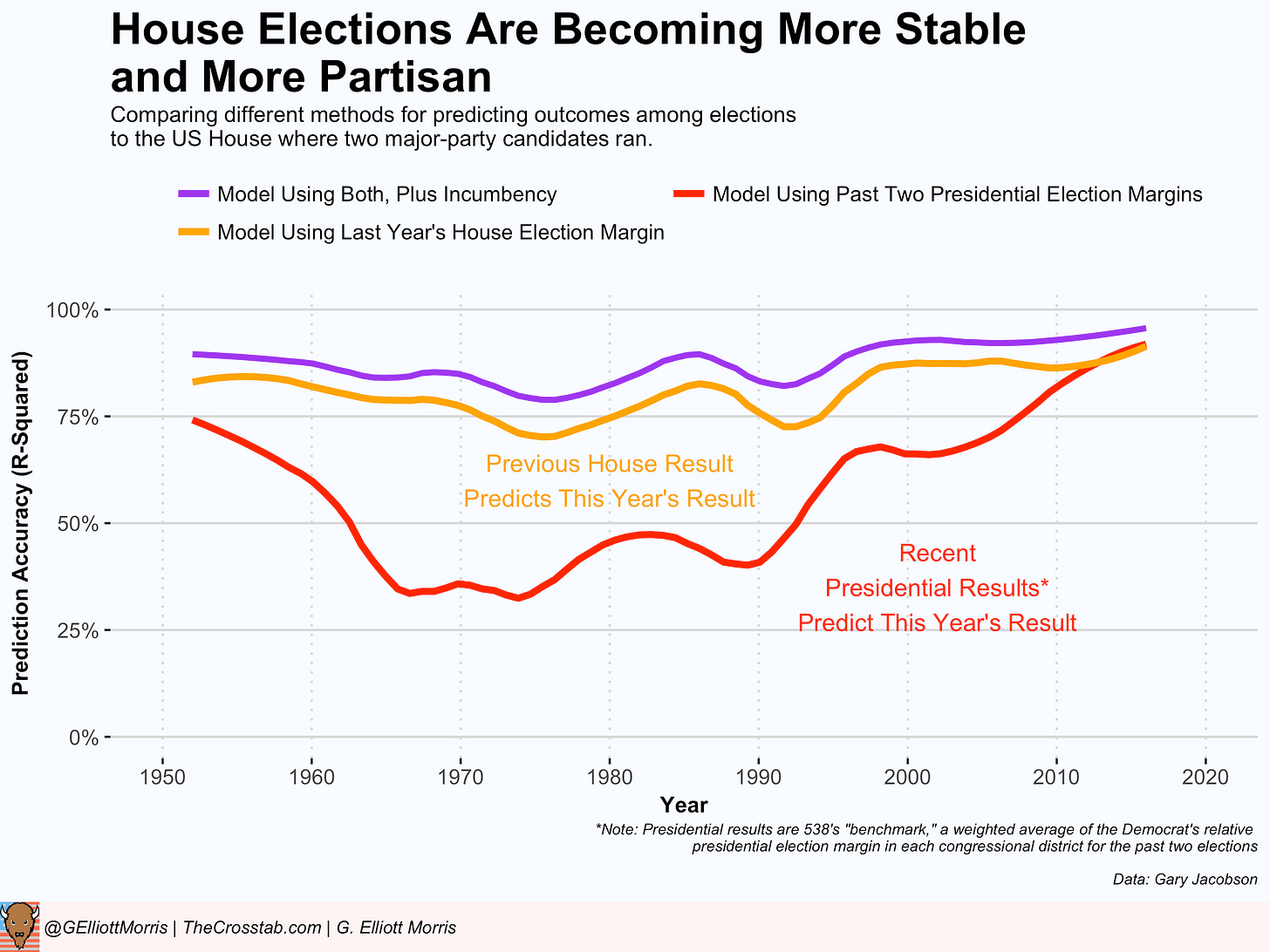

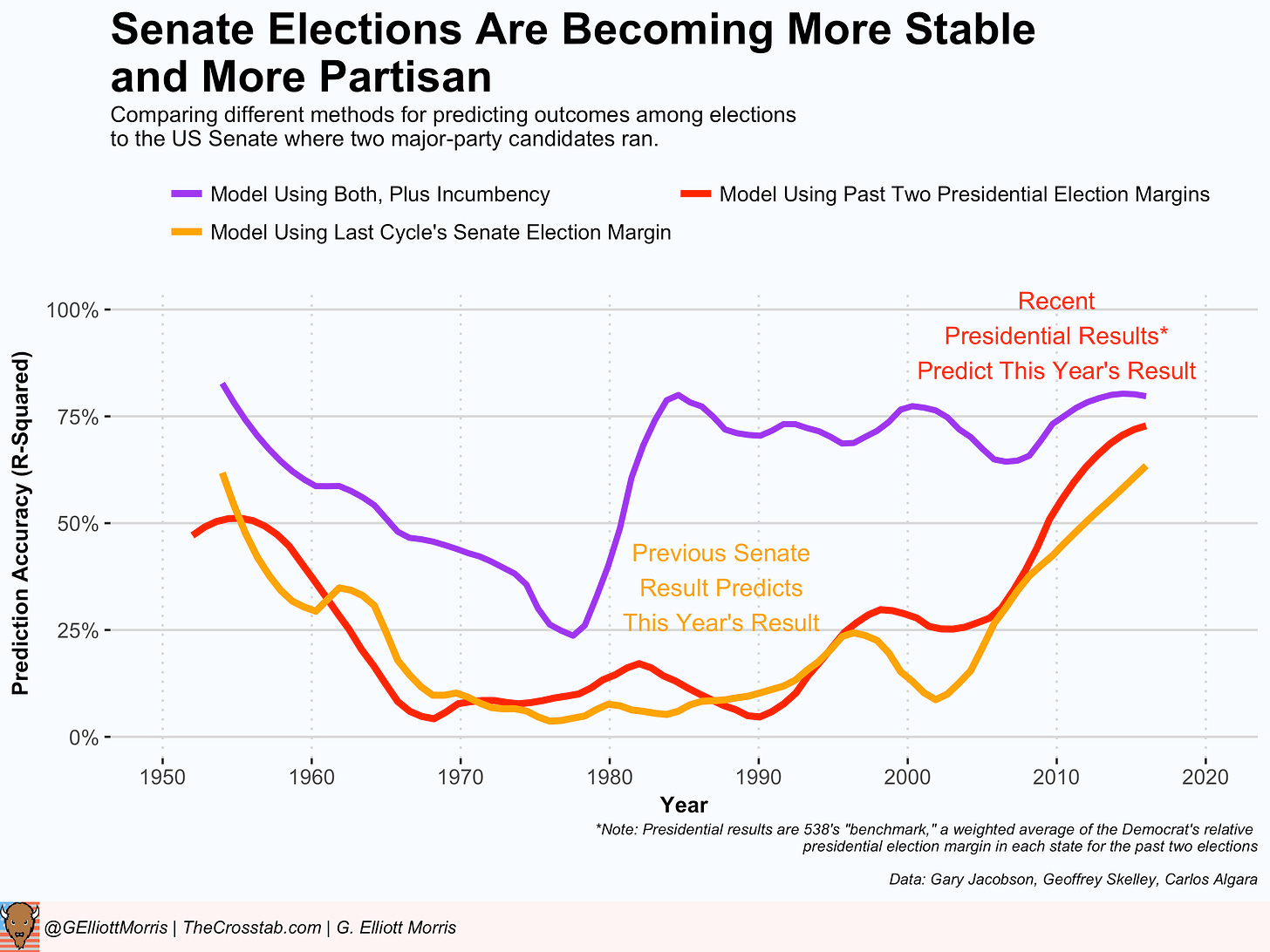

One crude way to look at nationalization historically is to measure the correlation between a Congressional district’s two-party vote for its Democratic House member/challenger and how it votes for Democratic presidential candidates. You can do the same for Senate elections. Here are two charts on this from a very old blog post of mine:

You can see a big increase in the explanatory power of presidential election results on House and Senate races since around the 1990s. Political scientists trace this to various causes which may include the rise of 24/7 cable news, the internet, and social sorting — and how the parties (led by Newt Gingrich and the Republicans) started talking about politics in more nationalized terms.

This has big implications for how parties win power in our geography-based electoral system. In the past, the political scientist Jonathan Rodden shows in his book Why Cities Lose, Democrats had a higher chance of winning elections in rural areas (and Republicans in cities) because the national party brands were not as strong as they are today. It was much easier for candidates to establish local brands for themselves and overcome any costs associated with the brands of the national parties in their electoral jurisdictions.

While there is little such flexibility today, Joe Manchin is a real exception to the rule. He is able to win in a state that Donald Trump won by almost forty percentage points because he positions himself as an anti-Party Democrat. He disagrees with the socialists on everything, he disagrees with the liberals and moderates on process; he is the lone Senator to flatly oppose lifting the filibuster for bills on voting convenience and voters’ rights. And he regularly gets in high-profile spats with party ideologues to convey to West Virginians that he stands with them rather than Washington (to adopt the senator’s dichotomy, which I have some disagreements with…).

Enter the paradox. When left-leaning Democratic members of Congress send anti-Manchin tweets or get into spats with him on cable TV or in the New York Times, and he distances himself from the party, both are reinforcing the non-Manchin otherness of their Democratic Party label. And, yeah, that might actually be right on the policy merits — Democrats are closer to the median Senate Democrat than Manchin on most policy areas — but it is a problematic strategy electorally. That’s because it increases nationalization and, in turn, hurts the party’s ability to win conservative voters from more rural states — the ones that, like it or not (and I don’t like it!) control the Senate today.

. . .

There are two more things to say on this front. The first is to clarify that I think this is a legitimately tough paradox! There are no easy answers.Most legislators like to affect change when they are in office; If they are being stopped routinely by the same holdout in their party, it is reasonable to expect them to air their frustrations. But that will have political costs down the line. I imagine Democrats can make the calculations about their own best course of action better than I can. Of course, if they can’t…

The final note is to highlight that the Republicans don’t have this problem. Because their voters are more uniformly conservative, and they punch above their weight in the Senate and Electoral College, they are actually helped by nationalization rather than hurt by it. This is yet another example of how our geography-based institutions hurt the party that represents voters who are clustered in cities.

To wrap up, I do think Joe Manchin and Krysten Sinema are clearly out-of-touch with what most Democrats wants their party to do with the hard-fought power they have in Congress, especially given they are not likely to hold onto it past 2020. Joe Biden has decided he would rather have something than nothing, and has largely capitulated to the two of them in the recent fight over the Build Back Better budget reconciliation bill. But so long as we are stuck with the institutions we have, and so long as Manchinema are the Democratic Party’s marginal senators, I don’t see any other clear alternatives.

I read in some book that when a person would come to FDR imploring him to support a policy, he would say, "Make me support it." In other words, create the groundswell, get the votes, just generally create the parade that he would feel compelled to get in front of. This isn't exactly on point with this situation, probably, but there is no parade that the Democrats can create that Manchin will want to even watch given his political persona. The only solution is more senators. Unlikely as that may be, my naturally positive nature is hoping for a Hail Mary pass next November so we can pick up at least one more vote in the Senate.

One point on your Economist article.

It is not the Republican Party, as you point out here, which has a big tent coalition with inherent contradictions that can be exploited. It is the Democratic Party which leads a big tent coalition with inherent contradictions, and its these contradictions which are causing Democrats all their problems. The Democratic Party is simultaneously the party for well educated, well off, voters, AND: extremely progressive whites, AND: relatively conservative minorities, AND: rural minority voters. These 'wings' of the Democratic Party do not share the same values, the same needs, nor the same desired policy outcomes. As a result, they cannot decide what's important.

A well functioning Republican Party would woo relatively conservative minorities away from the Democratic Party...this may be happening (we shall see if new GOP voters from 2020 were a blip or a trend). A well functioning Democratic Party would prioritize what it needs to keep its marginal voters happy. But the Democratic Party is not well functioning. Joe Biden is a back slapping old deal maker, but I have not been impressed with his ability to prioritize. Instead Joe Biden has attempted to be all things to all wings of the Party. He's already disappointed African-Americans...largely because their wants (a new Voting Rights Bill) is being blocked by Joe Manchin, and his new spending bill is not likely to satisfy anyone.