Democrats will win more votes passing popular policies than compromising for bipartisanship's sake 📊 January 31, 2021

Research shows voters reward politicians for improving the economy and passing popular policies, and don’t care much about how it happens

Thanks as ever for reading my weekly data-driven newsletter on politics, polling, and democracy. As always, I invite you to drop me a line (or just respond to this email) with any thoughts worth sharing. Please click/tap the ❤️ under the headline if you like what you’re reading; it’s our little trick to sway Substack’s curation algorithm in our favor. If you want more content, I publish subscribers-only posts once or twice a week.

Dear reader,

I write to you amid heavy white snowfall in Washington. Earlier, I went out to buy soup and made a small snowman. Click here to enjoy.

This week will be an important one in DC. Democrats’ decision to either proceed with a $2T stimulus bill or bow to Republicans’ counter of $600b will tell us a lot of how they plan to legislate for the next two years. In this newsletter, I look at evidence that collectively argues that they should do whatever generates the best economic returns and whatever is most popular according to the polls. In doing so, they should ignore demands for bipartisan “compromise” on the grounds that the public wants it; The reality of the evidence, as we’ll see, is that the people want their policies to pass and they don’t really care how that happens.

I hope everyone is staying as safe and warm as possible during the dark winter months. The good news is that now, with a competent bureaucracy and several covid-19 vaccines, we can clearly see the light at the end of the tunnel.

—Elliott

Democrats will win more votes passing popular policies than compromising for bipartisanship's sake

Research shows voters reward politicians for improving the economy and passing popular policies, and don’t care much about how it happens

The debate over the filibuster continues to rage among politicians and the political commentariat. Defenders argue that it’s a rule with a long history that prevents a slim Senate majority from oppressing the minority, while those in opposition (which includes the majority of voters) say that it gives the minority too much power over the process and benefits Republicans disproportionately because of their persistent geographic advantage. Detractors also make a pretty good argument that majority rule is the only tenable legislative system in a democracy, and the supermajority requirements is working to the detriment of that rule, so it should go. (For what it’s worth, you can count me among the many other political analysts and academics in the latter camp.)

As it turns out, political scientists are pretty smart and insightful people, and their research has a lot to say about these political calculations that many Democratic officials are making right now. Is it worth delaying progress to pursue bipartisan solutions?

Let’s briefly discuss two things: the popularity and positive electoral consequences of macroeconomic expansion, and the concerns about the appearance of unilateral policy-making.

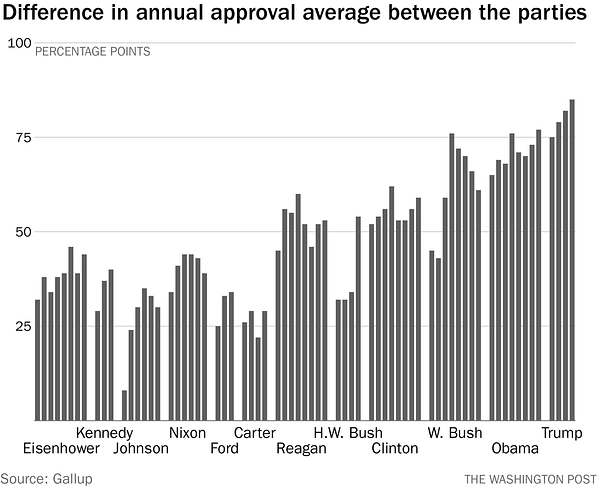

For starters, we should recognize that a healthy economy confers a significant advantage to the party in power. We find evidence for this claim across disciplines: political prognosticators have long used economic measures like growth in the gross domestic product and per-capita disposable income as predicts in election-forecasting models; economists have evaluated claims that presidents manipulate the economy to boost their re-election prospects; and political scientists have shown that improvements in economic conditions (typically from pork-barrel spending) increase support for Congressional legislators. In 2020, it seems like the relative stability of per-capita income (eg when compared to, say, the unemployment rate) may have helped Donald Trump fare better in his re-election attempt than economic growth otherwise predicted.

What should we take away from this? The finding that presidents benefit from improved economic conditions maps pretty neatly on the Democratic dilemmas both over whether to eliminate the filibuster and if they ought to unilaterally pass a nearly $2T economic stimulus, or whether they should “compromise” with Republicans and pass a much smaller $600b bill. The research we’ve reviewed so far would suggest that Biden and his Senate co-partisans should just go for the bigger bill and disregard concerns over processes.

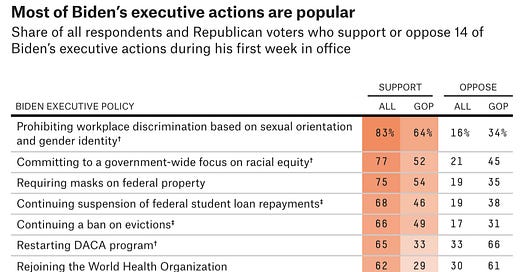

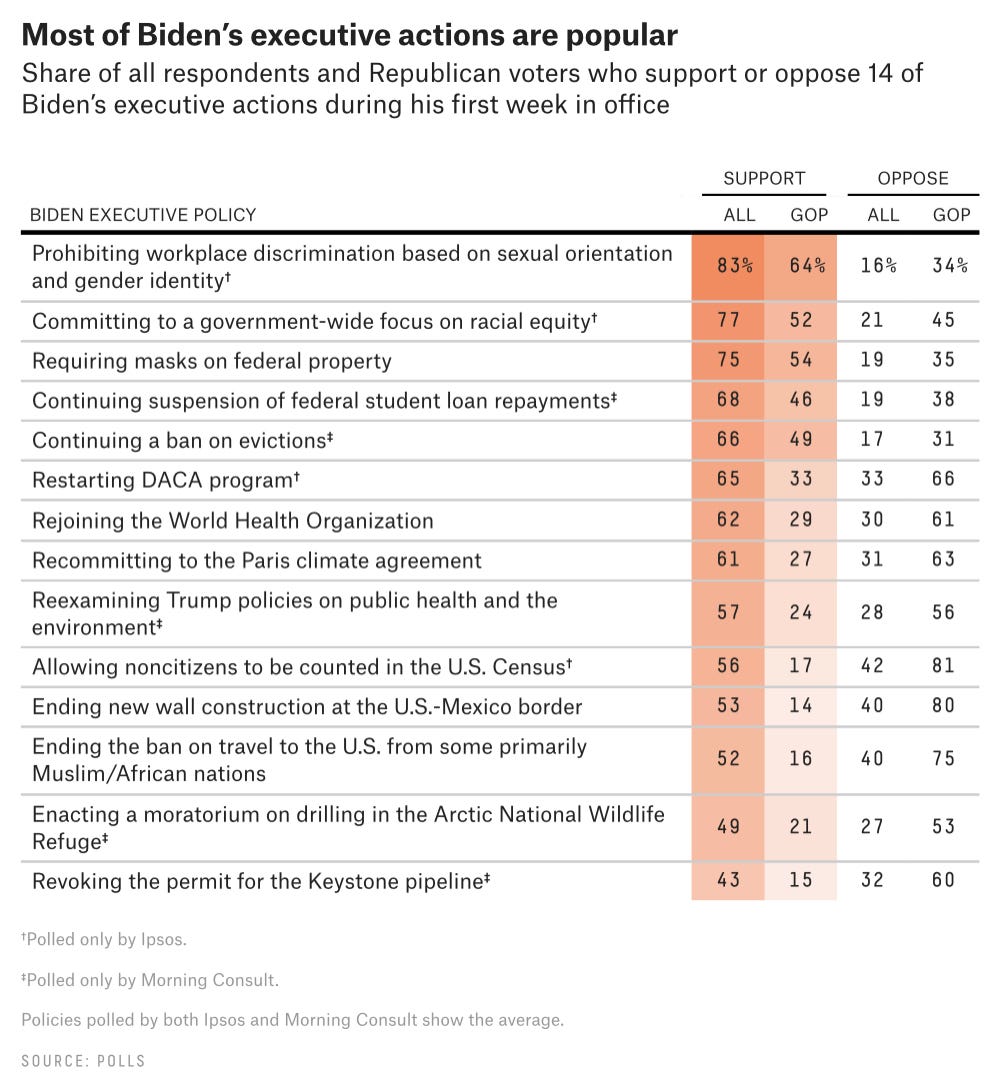

Further, it’s worth considering that almost every element of Biden’s agenda enjoys plurality support among all American adults, and most are popular with a majority. That’s true even if you adjust the polls for being biased toward liberal opinions (which they probably are). Here’s a graph from Perry Bacon Jr:

Despite the future benefits and current popularity of what Democrats are trying to do, there is some concern over the electoral tax they might pay for doing it without bipartisan support on Capitol Hill. I think this debate is a bit of a misdirection, however. One 2014 study from political scientists Laurel Harbridge, Neil Malhotra, and Brian Harrison found that voters are more concerned with getting what they want out of Congress than getting it through bipartisan processes. To quote two rather lengthy portions of their paper:

Both public opinion polling and the academic literature on institutional evaluations and procedural justice would have us believe that people prefer bipartisan policies because compromise is perceived as a virtuous quality. However, this is not what we found. Bipartisan legislation is not preferred over partisan wins and partisan-dominated coalitions. Further, when the extent of the compromises in the policy process was made clear to people, bipartisan legislation was actually preferred less than a partisan output because it is equated to a loss for one's party. These results are much more consistent with theories in political psychology on partisan goal seeking and partisan social identities, pointing to the importance of integrating studies of institutions, legislative behavior, and political psychology.

They go on to write:

Our results raise questions about whether majority parties will be rewarded or punished for pursuing partisan policies. As noted by Adler and Wilkerson (2013), lawmakers believe that voters value problem solving in governing; as a result, the party leadership cares about addressing the needs of the country and passing legislation. However, if legislation with partisan coalitions is easier to pursue than bipartisan coalitions and there is no bonus in support for creating a bipartisan coalition, partisan problem solving is the likely outcome. Beyond better understanding the basis of partisan conflict in government and the implications for representation, understanding public preferences over this politically consequential issue has important implications for scholarly theories and models of elite behavior. Having a more nuanced view of public preferences for moderation, compromise, and bipartisanship can help us better understand the motivations of political leaders and the outcomes that occur when the public is an important audience or actor.

I don’t know about you, but that latter bit sounds like a pretty perfect encapsulation of the current debate in Washington.

So long as we’re viewing the debate through the lens of potential public accountability, if the question is whether Democrats should choose to nuke the filibuster to pass policies that the people think are popular and would benefit them electorally, or whether to bow to Republican demands and forgo pursuing several parts of their policy agenda, the evidence is pretty clear about the better option.

Nuke the filibuster. Pass the bills. Enjoy the benefits.

Posts for subscribers

January 30: How popular are progressive policies, really? There are several reasons to think polls might overestimate support for left-leaning opinions

January 21: How strong is Biden's mandate for change? Polls reveal that the newly-inaugurated president has quite a lot of leverage

What I'm Reading and Working On

Do you know that old saying "There are three kinds of lies: lies, damned lies, and statistics?” Michael Wheeler borrowed it for an eponymously-titled book that railed against polls way back in 1976. I thought I would like it, but frankly, it is a thoroughly unimpressive book that blows the many weaknesses of early surveys way out of proportion and doesn’t bring much, if any, evidence to the argument. That being said, I agree with him when he writes that polls are “so fundamental to a democratic society that we must understand its full dimensions, its shape and texture.” Though Wheeler wrongly concludes that polls fail basic tests to make them useful mirrors into which we peer for our own national reflection, and should therefore be abandoned, it is healthy to remind ourselves to be reasonably skeptical about important tools so that we will constantly re-evaluate our methods to make sure they’re working properly.

In other news, Monday is the start of an exciting month for me. I return to work at The Economist tomorrow, February 1st, after three months of leave to write my book on polling. If fortune is in my favor, I will finish my draft manuscript by the end of the month — a reasonably attainable goal as I have just under 10,000 words left to write. I’m also giving a few more lectures on polls for the new semester (which I am always happy to do — just send me an email) and starting a few new academic projects with several people I admire. Cool stuff!

Other links and recommendations:

Two things worth checking out this week:

That’s it.

Thanks for reading!

Thanks for reading. I’ll be back in your inbox next Sunday. In the meantime, follow me online or reach out via email if you’d like to engage. I’d love to hear from you. If you want more content, I publish subscribers-only posts once or twice each week.

Hi Elliott,

I think Democrats have learned lessons from the Republican obstruction during the Obama Presidency. Even Biden himself appears less interested in working with Republicans if they outright reject his policies and threaten to undermine his agenda. It is likely that Democrats will end up using reconciliation to pass a COVID relief bill.

Republicans want to be able to hit Democrats in 2022 and in 2024 because Biden didn't get enough COVID relief. This worked for Republicans in 2010, when Republican won back the House with a large majority and picked up Senate seats. Republicans thought the worse Obama did in handling the recovery, the more Republicans benefited electorally. I don't see any reason why Democrats should not pass COVID relief or other popular bills based on a policy or electoral perspective.

I look forward to reading your book when it comes out!

-Elliot